1. School is mostly about indoctrination into the national identity. It is also about child care, and for older children, about keeping them out of the labour force. If we were honest we could talk about education policy with this in mind, though no one does (okay, there are some exceptions).

2. Gossip is a fantastic coordination device, allowing us to find like-minded others by bitching about particular issues or other people. The underlying idea here is that “my enemy’s enemy is my friend”, so if someone wants to have a good bitch, they are likely to be similar to you. Could be one factor in homophily observed in social networks. Again, rarely discussed.

3. The tax debate is 99% about distribution, 1% about growth. Don’t let economists fool you with their models that they don’t even pretend capture real phenomena. When they say lower corporate taxes increase growth they are modelling a world without assets where all profits are devoted to new investments in capital equipment.

4. Microeconomics is no more scientific than macroeconomics, particularly when it comes to theory. When people say there is progress in micro they mean in applied psychology, where experiments are widely used, and in empirical work where new data is helping to answer localised questions.

Most microeconomics though is still about markets, where aggregation of individuals is still a huge problem - it’s just a different level of macro.

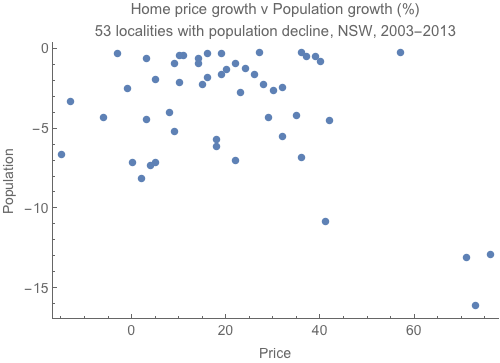

5. Farmers are one of the wealthiest groups in the country and we shouldn’t prop up their businesses or lifestyles (see chart below). They are not charities and will jack up prices when they can. We can protect food production as an industry by protecting the degradation of the land from incompatible and irreversible uses like mining, housing developments and so forth. But some farm businesses will go broke from time to time and that is not a problem. We also are a massive food exporter, so there is really no “Australian food security” argument.

6. Speaking of food security, we really overlook the main cause of malnourishment is poverty, not a lack of food production in the aggregate. Making poor people richer by taking from the top few percent of wealthiest and giving to the bottom 20% of the world would solve food security, amongst many other social ills.

7. Redistribution of global wealth is clearly the most obvious policy for a utilitarian. Bloody obvious.

8. Open borders to me seems like a way to pretend to be serious about global poverty and inequality. It allows supporters to pretend that the borders of private property within a nation are moral, yet the borders between nations are not. Somehow if I am denied, through accident of birth, to make a living from my share of the land in my own country, this is a radically different thing to Alex Tabarrok’s view, where he asks “How can it be moral that through the mere accident of birth some people are imprisoned in countries where their political or geographic institutions prevent them from making a living?”

As I have said before, even the wildest proponents of open borders agree that

“…open borders could not on its own eliminate poverty and that international migration could only help the relatively better off among the global poor”

Then what is it really for?