But simply talking about the housing market as if it is some monolithic beast will lead you to the error of conflating three distinct markets that must be considered independently to truly understand what is happening. These markets are

- The land/property asset market

- The housing service market (annual occupancy from rent or ownership)

- The residential construction market

So when we talk of high demand for housing, home prices increasing, and housing bubbles, we must be clear about whether we are 1) talking about the market for the land asset component of the bundled housing good, or 2) referring to the housing service market for occupying homes. Conflating these two markets is the most common error in housing market analysis and leads to conclusions that make little sense.

For example, take the frequent comments about the effect of population growth on home prices. To me, it is utterly confusing. If we are talking about the land asset market, the question then arises about why we don’t talk about the population effects on equity and debt markets, derivatives markets, and other asset classes that could equally see effects. Why would "new" people be willing to pay more for the same asset?

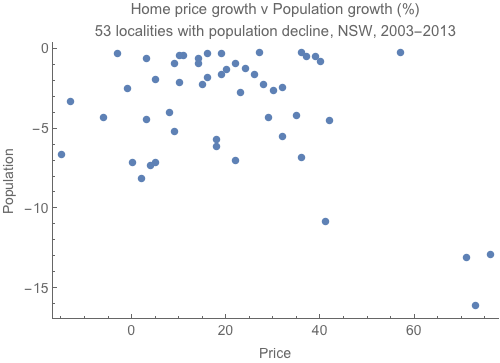

You can see from the graph below that population effects don’t seem to be a major driver of land asset price growth. Areas with a 10-15% population declines have still seen 70% growth in home prices.

Luckily, we do have a market for housing as a produced good that we consume on an annual basis quite apart from the land asset; the rental market. If we measure how much of our incomes we spend on rent, and the quality of the homes we reside in (in terms of area per person), we can apply the supply and demand model to the market. If there really is something going on with population and housing production, it must be observable in the rental market. Looking at the chart below we can see that the rent-to-income ratio declined all the way through the land price boom of the early 2000s. So too did the occupancy rate (fewer people per home) indicating that in Australia more new homes were built than needed to house the new people to the same standard.

So sure, use your supply and demand analysis on the market for produced durable housing goods, but remember that home prices are not the price in that market. Rents are the price in the housing market, while home prices mostly reflect asset prices of the land market.

Lastly, we can look at the construction market, which is driven by trends in other markets, including speculation on land markets. Here the supply and demand approach also works, as periods of high demand for new construction result in increasing construction prices (as demand shift to the right against a resource-constrained upward-sloping supply curve for construction services). But again, the construction market and construction prices are not the main contributor to growth in home prices. In fact, higher construction costs will decrease the value of the land asset, as they provide an additional cost to capturing future income flows.

The situation now in Australia is that asset market dynamics, including lower interest rates, international buying by investors whose return is more than just financial (hence will buy with a lower yield), and simple cyclical timing of investments, are driving up land prices in some capital cities. In some areas, when this asset buying occurs in new homes it also increases demand for construction, pushing up prices in that market as well. But in the housing service (i.e. rental) market, the additional new home construction is suppressing rents.

This is the way to analyse housing markets. Don’t be drawn into the monolithic view by conflating behaviour in these distinct markets.

There is a relationship between house prices and land prices that isn't made clear from your post. This post may help make it more clear:

ReplyDeletehttp://ochousingnews.com/blog/valuation-of-lots-and-raw-land/

The value of a piece of land is whatever is “left over” after all the other costs of production and profits are subtracted from revenue. This is a key point. Land for residential home use has no intrinsic value. It is a commodity useful for the production of houses just like lumber or concrete. A finished lot is a manufactured product, and it is subject to many of the same market forces as commodity markets. If land or lots become scarce, the price increases; if this commodity is plentiful, the price decreases. If the sales price of the final product increases revenue–like in a bubble–the value of land increases; however, if revenue decreases–like after a bubble–the value of land decreases. For a given price level, if the cost of house construction increases, the value of land decreases; if the cost of house construction decreases, the value of land increases. This last point is often confusing as the inverse relationship between building cost and land value does not seem intuitive, but since land value is a residual calculation, this relationship is the reality of the marketplace. The value of a piece of land used for residential housing is directly tied to the revenues and costs of house construction.

That's right Larry. I didn't want to dwell on the idea of land as the residual value here, but focus on the 'many markets' idea. I am trained as a valuer so have this very conversation with my economist colleagues on a regular basis ( who think about home prices as the result of adding up costs).

DeleteI may post again to clarify this point, though have covered it a few times before.

Very interesting post, Cameron, and very interesting response, Larry.

DeleteHowever, if we are thinking broadly about economics and the linkages between ecology and economics, we should be careful about statements such as "Land for residential home use has no intrinsic value." Strictly speaking, all land has intrinsic value for something - be it housing, farming, forestry, mining, ecological services, etc. Certainly, the prices of that land for various purposes are certainly highly influenced by the cost of production of those various commodities, but there are intrinsic values of ecosystem production functions involved, too. I can't farm a highly saline desert, but I can farm a nice loam on level ground in a temperate climate. When we analyze the trade-off between land-uses, such as conversion of agricultural land into residential land, we should be cognizant of those intrinsic values.

Very interesting post, Cameron, and very interesting response, Larry.

DeleteHowever, if we are thinking broadly about economics and the linkages between ecology and economics, we should be careful about statements such as "Land for residential home use has no intrinsic value." Strictly speaking, all land has intrinsic value for something - be it housing, farming, forestry, mining, ecological services, etc. Certainly, the prices of that land for various purposes are certainly highly influenced by the cost of production of those various commodities, but there are intrinsic values of ecosystem production functions involved, too. I can't farm a highly saline desert, but I can farm a nice loam on level ground in a temperate climate. When we analyze the trade-off between land-uses, such as conversion of agricultural land into residential land, we should be cognizant of those intrinsic values.

But the price of land isn't simply a function of supply and demand, Larry. It's that part of land rent remaining in private hands (after rates and land tax) which is capitalised into land price. Were we to publicly capture all land rent, theoretically there're no land price, but it's impossible to capture all land rent, because it tends to grow and have a residual as it's captured because economic performance also improves.

DeleteIn Seattle we suffer the worst of housing hyperinflation by from massive job increases (Amazon 24,000) with international speculative buying (China), restrictive geography forcing sprawl, developers speculative demolition and building tiny cubicle homes, rents tripling, along with a flaccid government incentivising all of it. You didn't mention the percentage of income for housing (even for two income families) still amounts to more than 50% of income making it impossible for families to meet future claims on income on home assets. It's that shrunken buying power that shrinks economies.

ReplyDeleteThe victimization of populations worldwide are the result of speculation of an "asset" that we know is the one foundational assets we need to pursue the rest of our dreams. We're not talking widgets here. This makes us easy victims to this artificial price manipulation to the point of delusional thinking that these prices will hold.

Hyper inflated housing prices, stagnant wages, and eventually saturated housing markets will lead to the inevitable price collapse economists are telling us about. There's going to be a lot of young couples stuck with brand new $800k cubicle style homes they'll never find a buyer for. The fallacy of supply and demand for housing will come clear when you learn that dreams burst exactly the same time deceitful speculative "bubbles" do.

The best solution is to take these critical assets out of the hands of criminal speculators and take control of them ourselves. The only way to insure accurate pricing on these assets is to use public housing for a majority of these assets. Combine that with national health care and utilities, and retirement, we will finally be free from the immoral corporate Wall Street squeeze. It's this horrific squeeze that keeps us chasing the rent only to feed the Wall Street monster. Wall Street knows fraud is legal now to enable Ponzi schemes.

That's why only a major shift in asset control back to citizens can keep prices sustainable. Simply the best system at the best price.

Only when we have control of life's necessities can we safely tell Wall Street they can make all the useless widgets they want.