Monday, November 1, 2010

Australia not an island away from world’s troubles – recession, bank runs, and printing cash

Thursday, October 28, 2010

Nothing is so firmly believed as that which least is known - or why changing your mind is evidence of learning

For a second, consider of all our major public thinkers today. They do the opposite, constantly telling how sure they are of their beliefs and criticizing their “opponents” for changing their minds. Changing your mind is a good thing, Montaigne would say. It means you’ve resisted the impulse to think you’re infallible. He wrote that as part of his profession of getting to know himself he found such “boundless depths and variety that [his] apprenticeship bears no other fruit than to make me know much there remains to learn.” If only we could internalize that attitude—instead of feeling cocky when we learn something, acknowledge that it really just taught us how much more we need to learn. (here)While I often use this blog to vent frustration, propose new ways of looking at problems and possible unintended consequence of our actions, this does not mean that my ideas and opinions are as fixed once published. Indeed, if I look back at some of the opinions I held some years back I can imagine a heated debate between current me and previous me.

For example, for a period of time, I had a fixation about peak oil and what it meant for society. I thought in a linear manner, ascribing a reduction in total economic production possible to a reduction in technically possible rates of oil extraction, without thinking of behavioural responses and adaptations likely to take place including a renewed demand for alternative resources. My last post clearly shows that I have edged away from that view to a more reasoned and 'systems' view of economic behaviour.

I used to be passionate about ‘sustainable’ living (whatever that means). If we could only all do our little bit our environment, in the holistic sense rather than just the trees and animals sense, would be a better place to live. However, with more research into the matter it appears that while my own choices are the only ones within my control, there are offsetting effects from the actions of others that may render my personal actions ineffective.

While my ideas evolve slowly as I seek evidence one way or another, I can’t help but marvel at how quickly strongly held beliefs can change in a time of crisis, even when evidence for the new idea is as sparse as the one previously held.

Tuesday, October 26, 2010

CPI surprise

Monday, October 25, 2010

Zombie Economics

Wednesday, October 20, 2010

No limits to economic growth

While I don’t doubt the finitude of many natural resources, and that the human population cannot grow indefinitely, I doubt that finite limits of resource inputs to the economy necessarily means that economic growth cannot continue indefinitely.

To be sure, I am certain that substantial unforeseen changes to the rate of extraction of some resources will lead to short-term disruption of established production chains, such as shocks to oil supply, but in the long run I see no reason that an economy with finite resource inputs cannot increase production through improved technology and efficiency.

I need to be clear that when I talk of economic growth I mean our ability to produce more goods and services that we value for a given input. Increasing the size of the economy by simply having more people, each producing the same quantity of goods, will be measured as growth in GDP, but provides no improvement in the material well being of society.

A better measure of growth is real GDP per capita. This adjusts for the disconnection between the supply of money and the production of goods, and adjusts for the increase in scale provided by the extra labour inputs. Even then, this may overestimate the rate of real growth occurring, as there has been a trend of formalising much of the informal economy, for example child care, which is now a measured part of GDP rather than existing as individual family arrangements.

On these adjusted measures economic growth is a very slow process. In a world where non-renewable resource inputs are fixed or declining, it is the rate of the decline and the speed of adjustment that will determine the overall outcome for our well being. If the rate of decline of non-renewable resource inputs is below the rate of real growth (our ability to produce more with less) and the rate at which we can substitute to renewable alternatives, we can avoid economic calamity in the face of natural limits.

Unfortunately there are other factors at play.

The rate of population growth will greatly determine the per capita wellbeing in a time of limited growth. While extra labour input will no doubt contribute to production inputs, my suggestion is that this input will be outweighed by a decline in complementary resource inputs. Remember, we care about real economic ‘wealth’ per capita, and with more people there is a smaller share of remaining resources each person can utilise in production, thus reducing wellbeing.

Further, we can begin to take productivity gains as leisure time instead of more work time, thus there is a possibility of maintaining a given level of production in the economy with fewer labour inputs over time.

There is also the reliance of our financial system on high levels of growth. Many economic growth critics cite the need for exponential growth of financial measures of the economy as being in conflict with any finite system. Yet the ‘system’ itself is a human construction and I seen no reason why a stable money supply cannot operate under various levels of growth (even prolonged negative growth) if used cautiously and with little leverage.

Often forgotten is that many resources are currently fixed and yet go unnoticed. There are always 24 hours in a day, but that doesn’t stop us producing more each day. If a shortage of hours was encountered, would a sudden change to 23hrs (a 4% decline) have a dramatic impact? Or would society easily adjust to this new environment of tighter time scarcity?

While a smooth transition to prosperity under much greater limits on resource inputs to the economy is theoretically possible, I don’t expect this to be our future reality. Self interested governments, businesses and the general public will react to short term shocks in unexpected ways, potentially promoting conflict, and taking the bumpy road. I have no doubt that there will extended periods of prosperity in the future, but also expect a rough ride to get to them.

Monday, October 18, 2010

Counterintuitive findings?

Wednesday, October 13, 2010

Murray-Darling Basin Plan: Despite extreme lobbying, you can’t take water that does not exist

My point is, people are taking the cuts as real water then multiplying impacts to flow on industries then getting bigger and bigger impacts that border on ridiculous. These complementary agricultural industries are clearly already adjusted to any proposed cutbacks.

Monday, October 11, 2010

WEIRD people: Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, Democratic... and unlike anyone else on the planet

How much would you offer? If it's close to half the loot, you're a typical North American. Studies show educated Americans will make an average offer of $48, whether in the interest of fairness or in the knowledge that too low an offer to their counterpart could be rejected as unfair. If you're on the other side of the table, you're likely to reject offers right up to $40.

It seems most of humanity would play the game differently. Joseph Henrich of the University of British Columbia took the Ultimatum Game into the Peruvian Amazon as part of his work on understanding human co-operation in the mid-1990s and found that the Machiguenga considered the idea of offering half your money downright weird — and rejecting an insultingly low offer even weirder.

"I was inclined to believe that rejection in the Ultimatum Game would be widespread. With the Machiguenga, they felt rejecting was absurd, which is really what economists think about rejection," Dr. Henrich says. "It's completely irrational to turn down free money. Why would you do that?" (here)

A recent paper by Dr Henrich and colleagues from the University of British Columbia investigates the psychological differences between WEIRD societies and other societies. In a deep examination of the literature, Henrich shows that while many basic similarities remain common to Homo sapiens, cultural factors play a large role in determining many psychological dispositions. Such differences occur when examining fairness, individualism and cooperation.

For me one standout finding was that the income maximising offer for the ultimatum game (discussed in the introductory quote) was a mere 10% of the total sum for most cultures in the review, while in typical WEIRD cultures a 50% offer was income maximising (see graph below).

Wednesday, October 6, 2010

Effective marginal tax rates and Australia’s welfare trap

So I took the time to examine situation for Australian families, and it is quite revealing.

This recent paper, for example, shows that the effective marginal tax rate (EMTR), which estimates the change in take home income after tax and after accounting for reduced welfare payments, actually declines at higher income levels for almost every family type (see table below). High income families receive a greater percentage of an extra dollar earned than low income families, with middle income families suffering very high EMTRs.

For example, an extra dollar earned by a parent in a family with two dependent children and an income in the middle tax bracket will leave them with an extra 28c in the pocket, while for a high income family, they keep 67c out of any extra dollar.

There are even situations in Australia where the EMTR is greater than 100%! Low income families with dependents on youth allowance have an EMTR of around 110% - for every extra dollar earned, they get 10c less in their pockets.

Unfortunately, I fall into the group with the highest EMTR – families with dependents – where 15% of the group have EMTRs above 70%.

...families with children are more likely to face an EMTR of 50 to 70 per cent than other types of households, due to the accumulation of withdrawal rates for family related payments on top of income support withdrawal and income tax. This is observed even without including the withdrawal of childcare subsidies. On average, the EMTR is highest for couples with dependent children. (here)

After a quick bit of research, it appears that if I earn another dollar we lose 20c from family tax benefits, about 18c in the dollar from child care benefits, and 30c in tax – a 68% EMTR. If my wife earns an extra dollar we lose 40c in Family tax benefits (Part A and B combined), 18c of child care subsidies, and 15c in tax – a 73% EMTR.

In light of this outrageous situation, cutting down to part-time work (4 days/week) provides an extra 48days of leisure per year at a minimal cost to the family.

Also, if we factor in the extra expenses incurred due to extra work hours and time pressure – takeaway meals, remaining child care costs, driving instead of cycling, and splurging on treats because you deserve a reward at the end of a busy day, you quickly see the rational for staying in the welfare trap.

All this makes me wonder just how many families are trapped in high EMTR bands – all earning different incomes, but taking home much the same income ‘in the hand’.

Monday, October 4, 2010

Statistics lessons for property people

In a recent bulletin to members he criticised the Local Government Association of Queensland’s interpretation of a report they commissioned on factors affecting home prices in South East Queensland.

He questions the conclusion that the AEC report commissioned by LGAQ refutes ‘for all time the spurious arguments of a so-called under-supply of dwellings in the SEQ market’. If he had paid attention in statistics it would be clear to him that this is exactly what the report does.

Although the report is far from an exemplary analysis of key determinants of residential property prices, the authors did estimate six econometric models to seek the determinants of real median house, unit and land prices in SEQ - eighteen models in total. If we quickly browse the report we find just one model, for house prices, not unit or land prices, where any of their supply-side variables is significant in explain real prices.

To be sure, Stewart’s interpretation of the report was poor, and his bulletin misleading, but I still have reservations about the report itself.

Particularly I have concerns about the choice of, and construction of, variables, including location bias in calculating the median prices and using ratios to total stock rather than sales volumes (particularly in the treatment of the FHOG). It seems odd that with 69 data points and 32 variables at hand they had trouble finding significant relationships in the data – could it be their selection was stacked with the wrong variables to explain prices?

One example of the construction of variable is ‘SEQ housing stock per capita’, which is total stock for SEQ at the beginning of the period at the beginning of the analysis (1991) of 734,126, less an allowance for depreciation (about 0.3%), plus new stock completed IN QUEENSLAND in the period. This variable then accumulates over time to represent the stock of housing.

I first hope that the new stock only includes new stock in the SEQ region and that this is a typo. Second, I can’t see how depreciating a dwelling is good accounting. What should be considered is a factor for demolitions, and it would be easy enough to estimate the demolition to new dwelling ratio based on past census data.

These types of errors abound.

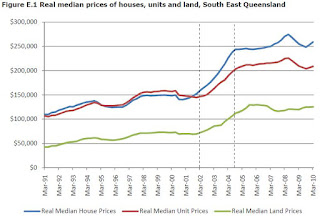

Most importantly I wonder how this controversial variable could be negatively correlated with prices. In the section on housing stock (p13) it shows that dwelling stock per 100 people grew from 38.1 to 41.1 from 1991 to 2006, while real prices grew from around $100,000 to $250,000 in this period (below). Either a) the three other significant variables, the All Ordinaries, unemployment and mortgage rates, explained the most of the change, or b) the variable used in the analysis is the CHANGE IN dwelling stock per person, which was positive but declining over the period.

What is further surprising is the conclusion that the SEQ property market somehow behaves differently to other parts of the country. Given that the analysis failed to explain the behaviour of the SEQ residential property market at all (their final land price model on page 29 had seven variables but just two were significant), one wonders how such conclusions are drawn. I am happy for someone to explain why it is different here (cringe) if they have the evidence to support the statement.

Anyone looking to elastify the supply side should note the report concludes by noting how responsive supply has in fact been to prices:

...the lot stock for SEQ rose from 25,000 during the early part of the decade to reach 50,000 by December 2005 and has stabilised around 54,000 since September 2007. This progression follows the growth in land prices very closely, indicating that supply of undeveloped residential lots has responded to price signals.

Thursday, September 30, 2010

Common sense and the CityCycle launch

Monday, September 27, 2010

Too good to be true environmental solutions

Sunday, September 26, 2010

Lessons for the RBA on their blunt instrument

... we only have one set of interest rates for the whole Australian economy; we do not have different interest rates for certain regions or industries. We set policy for the average Australian conditions. A given region or industry may not fully feel the strength or weakness in the overall economy to which the Bank is responding with monetary policy. In fact no region or industry may be having exactly the ‘average’ experience. It is this phenomenon that people presumably have in mind when they refer to monetary policy being a ‘blunt instrument.

I think poor old Glenn is taking his hammer to a screw.

While he wisely notes we have one set of interest rates, not one interest rate, he seems to ignore the fact that differentiation of interest rates on debt should reflect the risk for each particular loan. The problem for the RBA is that those who actually lend in the marketplace are failing to properly price the risk premium associated with their particular loans. Housing is surely a risky investment at the moment, yet interest rates do not reflect the risk premium.

The obvious alternative to shifting the whole set of interest rates is to better manage the risk premium rate for a particular industry of concern, or forcefully adjust risks taken with other measures to suit the rates adopted in that industry.

For example, if banks insist on lending for housing at relatively low interest rates, they can reduce risk by keeping lower LVRs and more conservative income estimates. If they won’t do it voluntarily, because they suffer from extreme moral hazard associated with guaranteed government bail-outs, maybe the RBA can seek to have banks better regulated with regards to housing loan risks, particularly qualifying income and LVRs.

At the moment increasing interest rates will simple increase the interest burden on current debts, high risk or not, decrease take up of borrowing for productive purposes, and fail to curb the mispricing of risk and crude lending criteria of housing loans with the major banks.

Thursday, September 23, 2010

What I have found interesting lately

Tuesday, September 21, 2010

Gaming leads to unintended consequences when governments try to stimulate housing supply

The aggressiveness of changes to planning instruments to allow for greater heights and densities, and allow fringe areas into the urban footprint, provided opportunities to profit simply from speculation on the next change to the planning scheme. For landowners it became more profitable to wait three years for the local government to update the planning scheme to allow greater density of development, than to actually develop the site.

One example, South Brisbane, epitomises this situation.

At this prime location, within a stone's throw of the CBD, the previous limits of 12 and eight storeys were already conservative.The planning scheme for this precinct has changed from allowing four storeys, to seven storeys, then proposing eight storeys, then twelve storeys in the latest draft plan, and now the UDIA is calling to increase the heights much further. With the approval of a 30-storey tower adjacent to Milton railway station, one could assume there is a long way to go in this saga.

Expectations were for this pattern to continue. A landholder in this area recently mentioned they have no reason to sell or develop when the council keeps increasing the value of their land by changing the planning scheme. Landholders are gaming the Council, waiting for a signal that the gifts will soon expire before selling up to developers.

Maybe that signal is here.

The State government has intervened in the latest round of planning scheme changes to request the proposed height limits be cut back – where 12 storeys was proposed, they will allow seven.

For anyone aware of the standoff taking place the flood of development sites onto the market in the month since the State government decision would come as no surprise. Who would have thought reducing height limits would promote so much development activity?

The moral of this story is that certainty (or lack thereof) can greatly change real outcomes. Economists often foolishly assume that all government decisions are taken at face value by the marketplace. Few realise the time element and that parties affected will already be anticipating the next decision, or gambling on a political backflip.

UPDATE: More evidence of rewarding land banking rather than productive land use, from the Local Government Association of Queensland -

The LGAQ today criticised a key provision of legislation introduced to state parliament on Tuesday which retained a 40 per cent rate subsidy for large companies holding big tracts of land approved for development but not yet formally subdivided.

The money at stake is not the issue here. The issue is the massive contradiction of rewarding developers for not sub-dividing land to increase supply when the state government says it is championing housing affordability issues

Sunday, September 19, 2010

Flow-on effects of recycling - are there net benefits?

Like efficiency, the word recycling reflects positivity from all angles. How could anyone say a bad thing about recycling?

I propose not to say a bad thing for the sake of cementing my identity as a super-sceptic, but to examine in detail the potential flow-on effects of recycling and determine whether the espoused benefits can theoretically be delivered.

Generally two benefits of recycling are proclaimed. First, waste will be diverted from landfill, thus we can reduce the space required for this purposed and reduce the threat of leaching from landfill sites into groundwater systems and other environments. Second, recycled material will substitute for raw materials and thus reduce consumption of natural resources which may have associated negative environmental externalities.

These are two distinct benefits, and achieving one does not necessarily imply achieving both.

There are also two different economic scenarios for achieving recycling with different outcomes – the profitable recycling scenario, and the unprofitable recycling scenario that requires government support.

The profitable scenario represents an improvement in overall economic efficiency, thus, like the case of profitable energy efficiency, it facilitates future economic growth and improves our productive capacity.

In this scenario, recycled material cannot be said to be diverted from land fill, because it would never have been put there in the first place due to the material’s value to remanufacturing. If the material was simply dumped on the street there would be an opportunity for a business to emerge to collect the material and sell for a profit. Without a counterfactual we cannot estimate the effect on either of our two recycling claims.

If we assume instead that the counterfactual scenario is one where the technology had not yet emerged to make recycling profitable, then we can now consider the flow-on effects from the technology. It is best to have a single material in mind, say glass, when thinking of these effects.

First, the price of the final goods (windows, bottles etc) using the newly recyclable material will decline due to the reduced cost of recycled instead of raw materials. Thus we will see an increase in demand (not a shift in the demand curve, but a new point on the demand curve at a lower price) for these final goods and therefore an increase in demand for recycled and/or raw materials (recycled glass or silica from natural sand deposits). Depending on the availability of recycled material compared to the total quantity of raw materials, this can lead to greater demand for natural resource itself (sand mining).

We can now say we have probably diverted waste from landfill leading to a greater quantity of material circulating in the hands of society (as either capital equipment – glass in buildings perhaps- or soon to be recycled consumables – maybe bottles), but we cannot say with certainty that the new recycling technology has reduced demand for the particular natural resource in question. Nor can we say that demand for, and consumption of, other natural resources remains unaffected. In fact the new recycling technology, since it improved overall economic efficiency, is likely to increase demand for all natural resource inputs to the economy.

The alternate unprofitable scenario represents a decrease in overall economic efficiency, and will reduce overall economic activity compared to scenario where government did not use its coercive power to enforce this unprofitable venture.

In this scenario we are likely to see a decline in waste to landfill compared to the economically efficient situation where recycling is not subsidised. We face the same situation of compensatory demand due to price declines of final goods manufactured using the cheaper subsidised recycled materials. This scale of this offsetting behaviour cannot be readily estimated and is likely to strongly depend on the relative prices and quantities of the recycled materials and raw material inputs are a particular point in time. A decline in overall demand for raw materials in the economy as a whole is certain in the unprofitable scenario due to the overall reduction in economic efficiency.

For unprofitable recycling the net result will be a reduction in waste to landfill of both the recycled good and other goods (since we can now produce fewer goods in total across the economy), and a reduction in resource consumption of the recycled material and all other resource inputs to the economy.

In what is becoming a familiar environmental theme at this blog, it should be clear that indirect measures to curb negative environmental impacts from our activities, such as promoting conservation behaviours, profitable energy efficiency, and recycling, have questionable net impacts on the environmental issue at hand.

Returning to our two main environmental goals of recycling – reduce negative impacts form landfill sites and reduce resource extraction that involves an environmental burden – we can clearly offer more direct measures which are both easy to establish and have certain environmental benefits.

The first environmental goal can be achieved by setting minimum environmental standards for landfill sites to address leaching (or any other associated problem depending on local conditions) including, perhaps, restrictions on location. In response to these criteria, landfill operators (public or private) would need to adopt appropriate measure to limit external impacts – possibly lining their pits with impermeable material, sorting, washing or removing particular types of waste, or some other creative response. These extra costs of waste disposal – the internalised environmental cost – will flow through to the cost of disposal, and may render some recycling programs profitable.

For the second environmental concern, resource extraction, similar direct controls can be used. Sticking with the glass example, the scope of sand mining can be limited through planning controls where natural environments which are valued by the community. Once this limit is established, sand mining in that area can proceed, at any particular rate, with certainty that there is a finite limit to the environmental cost.

These limits would never be, strictly speaking, perfect. They would at best reflect the perceived value of the environment to the community. There is no reason that the limits should not be stricter in some areas than others.

As an indirect environmental measure with questionable benefits, recycling, like efficiency, is claimed to be a panacea for a variety of poorly defined environmental ills. We often forget to critically examine the link between this indirect environmental ‘remedy’, and the target environmental illness.

Friday, September 17, 2010

A closer look at Australian incomes and predictions from Google Trends

Tuesday, September 14, 2010

Energy efficiency - further reading

Brookes also adds taxing resources to reflect the cost of negative externalities, which one assumes, would be spent on reparation activities to return to a new optimal resource allocation which internalises the cost of pollution and eliminates the possibility of rebound effects (if reparations are possible).

It is worth reading his conclusions in full (below the fold):

Sunday, September 12, 2010

Dutch Cargo Bike Review

Note: A follow-up (3yr) review is here. I am now a local ambassador for Dutch Cargo Bikes. If you would like to test rise this bike in Brisbane (or a three wheeler) email me at cameron@dutchcargobike.com.auI almost convinced myself not long ago that a bicycle for carrying children was a completely unjustified expense. Luckily I didn't. Because my sparkling new bakfiets.nl cargo bike, supplied through Dutch Cargo Bike, arrived several weeks ago. And I'm excited. I've also convinced myself that in reality it isn't expensive, and in fact represents great value for money.

fn.[1] The alert reader will note there is an opportunity cost to the forgone $3000 that could have been alternatively invested, say at 5%, which adds another $150 per year.

Wednesday, September 8, 2010

Energy efficiency: A flawed paradigm

Monday, September 6, 2010

Economist forecasts for the record

Sunday, September 5, 2010

Waste Revisited – the ‘Green’ bag revolution

Thursday, September 2, 2010

The Environment Revisited

For those new to the blog, the divergence of post topics from my blog title is explained here:

...understanding property is the key to a reasoned approach to preserving our quality of life by preserving environmental amenity. Maybe I am more of a ‘quality of life’ economist who believes there are many non-market goods, including the quality of, and accessibility of natural environments, that are major contributors to our well-being.

However the increasing fanaticism I have observed in some areas of the climate change movement, the lack of ability for some environmentalists to see the forest for the trees (pun intended), has lead me to distance myself from some of the core environmentalist views.

As a rule of thumb I believe we should first focus our efforts on local, tractable environmental problems with clear externalities, and implementable solutions – protecting diversity and fish stocks in the Great Barrier Reef, tackling air pollution and improving urban amenity, and preserving the quality of waterways and wilderness areas. Climate change, that global intractable problem, has dropped down my list of concerns, even though my previous research focussed on ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The development of my ideas on the environment is the reverse of renowned ‘skeptical environmentalist’ Bjorn Lomborg’s u-turn. He once held a strong position that climate change was far down humanities list of concerns, particularly noting the obvious an immediate threats from treatable diseases in the developing world. Now climate change to the top of his list, no doubt to pitch his new book to cashed-up fanatics.

My second rule of thumb is that personal ‘green’ consumption choices make no difference, and small actions do not add up. These behaviours are typically offset by other economic adjustments in upstream production and by choices of others as prices respond. These effects are know an rebound effects.

A recent article in The Economist highlights new research showing these rebound effects in action. The study estimates that new energy efficient lighting technology will increase energy consumption in the long run. My own research showed that conservation behaviour, such as using lights and electrical appliances and driving less, will also result in minimal change as money saved get spent elsewhere in the economy.

I intend to revisit ideas about waste, efficiency, environmental taxes, recycling and solar power over the next month to see how my ideas have developed, and to seek input to develop them further.