This is an excerpt from a new paper of mine available here.

What is the source of rezoning gains?

The answer to this question relies on understanding the nature and extent of property rights. A core right of a property owner is to exclude others. A right holder of this type usually also has a residual claim to income generated in the space over which they have exclusionary rights (“pay to use this space or I’ll exclude you from it”).

But these rights are limited. They evolve as the law evolves, including zoning and planning law. Rights to access and sell minerals within a property’s exclusive space, for example, are not part of the private property rights bundle in Australia. They are instead owned collectively by States.

The value of private property rights is primarily determined by how much revenue can be generated above costs (excluding property rights costs) on a site at a particular location. The value of property rights is a residual, just as other assets like shares in company ownership represent residual claims on income. Whichever use of a site generates the largest residual income is its highest value use.

The revenue potential of private property rights is affected by market conditions, location-specific features, fixed improvements, and the nature and extent of the property rights bundle itself. Investing in new fixed improvements, like buildings and earthworks, can add to property value because they remove a cost to gaining revenue (remember, property value is revenue minus costs needed to earn that revenue at that location). The value of fixed improvements becomes “attached” to the property as they cannot be separated physically or legally from the property right to a location.

However, the value of private property rights can also increase due to external factors that are not due to investments made by the property rights owner. When this occurs, it is known as betterment. For example, new public works that improve the accessibility of a location will increase the value of those sites because they reduce the transport costs of using those sites to generate revenue. Similarly, when the law changes the nature or extent of property rights in a way that increases the revenue-generating potential of that site, such as with rezoning, the resulting increase in value of the property rights bundle is betterment.

Planning rules coordinate property uses across locations by defining property rights bundles. For this coordination role to affect property uses it must legally restrict some uses so that the highest value legal use is different to what might occur with a “no zoning” property rights bundle. Hence, there is an inherent conflict between maximising the value of any individual property and coordinating the location of property uses across a region.

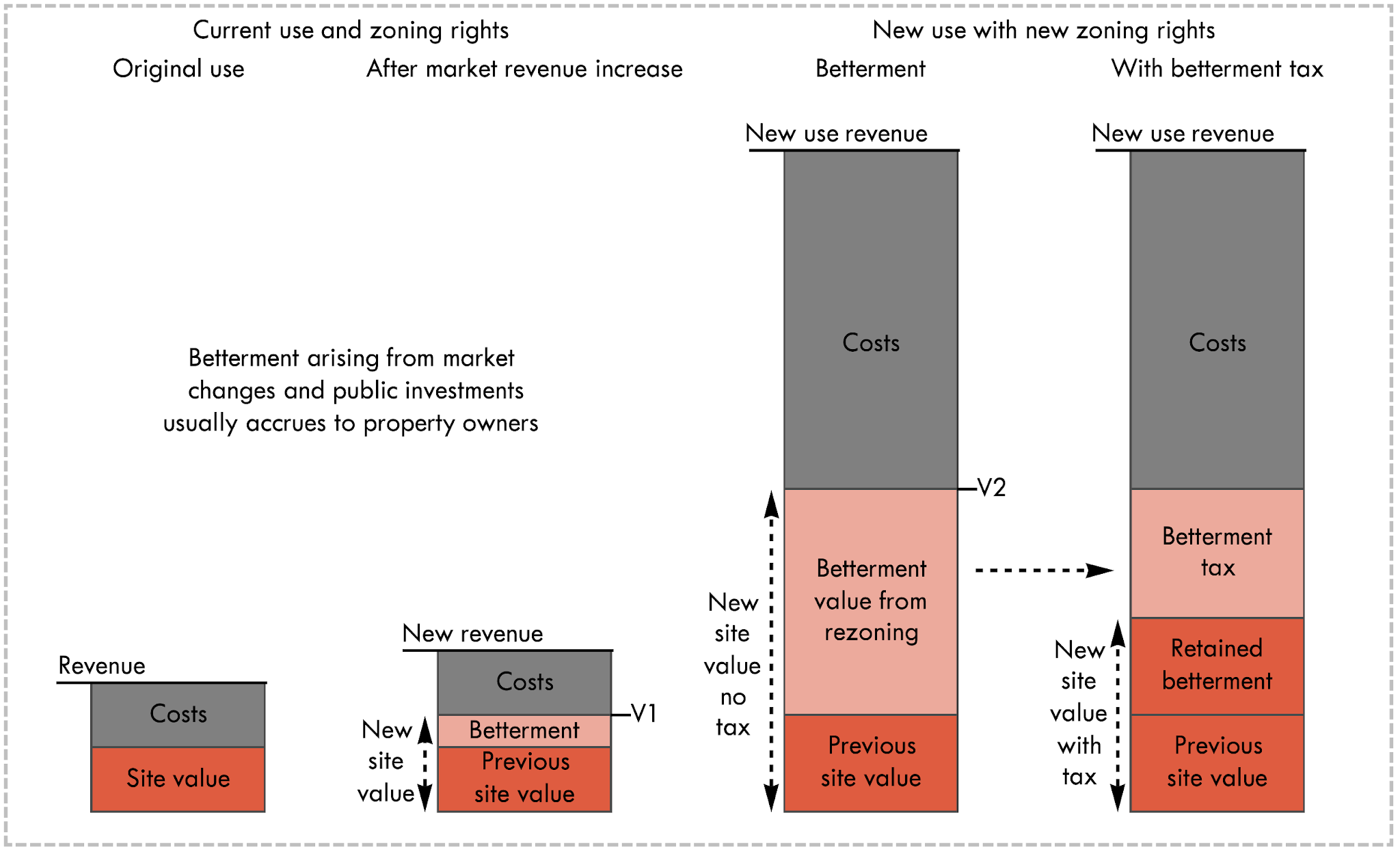

The diagram in Figure 1 shows how betterment arises conceptually and how a tax on betterment transfers value to the public that would otherwise accrue to private property owners.

Figure 1: Betterment in the residual model of property value

The left column shows the value of the property rights at a site, such as agricultural or industrial land. That value is determined by the revenue that can be made from exclusively using that site, minus the necessary costs. The site’s property rights value is the residual.

Suppose the market value of the output being produced increases, such as the value of crops on an agricultural property, but all input costs remain the same. In that case, the site value rises to reflect the higher residual value of production on that site. The new site value and its betterment component from these external factors is shown in the second column of Figure 1. Another example is if the rent of a residential dwelling rises, but the costs of operating that dwelling remain constant. This increases the property value. Where a property tax system exists, some of the value gains accruing to property rights from higher market prices of production are shared with the public.

The third column of Figure 1 shows what happens if there is a change in the nature or extent of the property rights through rezoning. For example, if the previous highest value use of a site was industrial only because zoning laws prevented other higher value uses such as residential, then rezoning will change the highest value legal use of the site and hence its value. The difference between the “before” site value (V1) and the new “after” site value (V2) is betterment.

A flexible planning system presents opportunities to increase revenue from development by exceeding codified density limits and hence offers another way to generate betterment for a landowner. The betterment gained from exceeding codified planning density limits is just as real as the betterment gained from rezoning. It is why, despite cost, risk, and time involved, many property owners seek planning dispensation instead of complying with codes and gaining fast approvals.

Here is a useful way to conceptualist betterment. Rezoning adds an additional private property right to the previously owned bundle. The value of this new right is betterment, and it reflects what the market would pay if these new property rights were instead auctioned for sale to existing property owners.

The effect of a tax on betterment arising from rezoning is illustrated in the fourth column of Figure 1 using the 50% tax rate proposed in Victoria. A share of the betterment value is transferred from the private property owner to the public, reducing the private payoff from rezoning decisions and increasing the public’s share.

The size of betterment from rezoning can be extraordinarily large, often many multiples of the previous site value. For example, a well-situated industrial site in Sydney’s inner west was bought for $8.5 million, rezoned high-density residential, then sold again just a few years later for $48.5 million.

Rezoning at Fishermans Bend in Melbourne led to numerous sites trading at values many multiples of their previous industrial use values. At 320 Plummer Street, Port Melbourne, the 7,468m2 site formerly used as the Rootes (Chrysler) factory transacted in 2009 for $1.7 million with industrial zoning rights. After rezoning to high-density residential, an application was made and approved for the development of three towers containing 443 dwellings and 908m2 of commercial floor area. The property was subsequently purchased for over $11 million. Even after inflating the 2009 sale price to $3 million to reflect sale prices in 2015 for similar industrial properties, the windfall rezoning betterment is roughly $8 million, with the site trading for nearly four times its previous value.

Notably, betterment is not an additional cost to housing development. The value of property rights is a residual; after all, there are no input costs to these rights. Betterment merely reflects the change in the market value of the residual claim on income of the property rights owner, and taxing betterment merely transfers this value from the property rights owner to the community.