In fact, if I was to be cynical, I would say many economists who attach themselves to the mainstream, in whatever specialist area that may be, are not interested in any consistency of ideas.

Also, many were taught economics in a way that never delved deep enough into the underlying assumptions that core models embody. Perhaps the effort to understand the mathematical representation of a model took away from effort to understand the conceptual ideas within it.

Unfortunately this set of circumstances is hindering efforts at reconciliation and consistency between economic tribes. I consider this post a ceremonial attempt at reconciling theories of debt across economic tribes.

In fact there are many concepts that are easily reconcilable (capital, uncertainty, emergent properties, savings, etc) but there are unfortunate incentives against unifying the discipline.

Debt

Currently there is much concern worldwide about debt. It is widely claimed that the mainstream economic community could not see a crisis coming because it fundamentally ‘looked through’ money and debt to the real economy. And since debt, or in fact the dynamics of debt, seemed an important factors in the crisis, this was a failure of the theory.

It is easy to agree with this critique. But to really understand it we have to disentangle all parts of it, and as we will see, there is an obvious way to reconcile the mainstream with the critique.

Household example

To begin, a theory of resource allocation is right to treat debt as an internal allocation mechanism of real resources in the economy.

In a my household, for example, I can lend my wife money to treat herself a new dress today. If we were accurately keeping internal household accounts that would be a transfer from myself to her. In real terms, my consumption of resources decreases and hers increases.

Next week the debt is ‘repaid’ according to our internal accounts when my wife lends me money to take the kids to the football.

When we look at our household as an aggregate entity, our total resource consumption is unchanged by the debt, which merely represents an internal reallocation.

There were no future resources brought forward for my wife to consume. The debt did not leave a cost to our children. Even if it was never repaid, I already paid for my household’s debt with the resources I didn’t consume when I transferred purchasing power to my wife.

It surprises me that on this crucial point the core mainstream concepts are consistent with the functional finance or modern monetary theory perspective, yet there remains animosity between these groups. I have come to believe that this is mostly a result of inadequate understanding of their own conceptual apparatus by the mainstream (here’s an example of how the noisiest mainstream commentators remain confused about their own theories).

Much of the mainstream has equated 'looking through' debt to the real resources of the economic with ignoring the money creation aspect of debt altogether. This has lead to further confusion in the analysis of banking and economics generally, with the Bank of England recently having to explain the process to the economics community.

These core economic concepts are easily confused when one fails to properly understand the complete accounting of the system at all points in time. Specifically the use of overlapping generations (OLG) models can confuse more than inform, and many students come away from learning these models believing in the possibility of inter-temporal reallocations of resources.

OLG example

To labour the point, the errors made in understanding the concepts at play in debt are evident in the overlapping generations models (OLG) which is commonly applied in economics in order to understand various internal shifts in resource burdens. It can be easily misunderstood to show that debt enables resources to travel through time.

Abba Lerner made the argument I am about to make back in 1961, when he was President of the American Economic Association. He was pulling into line economists Thomas Bowen, James Buchanan, and others, on their acceptance of the political propaganda that debt can distribute burdens across time. You’ve all heard a politician claim that debts are ‘leaving a burden for our children’.

The mistake of Bowen and Buchanan arises because of their incoherent conceptual application of the OLG model. In the model they merely redefine the current generation to mean those who lend the money, and the future generation as the one who pays the money (principle and interest) back.

Let me try and represent the model as simply as possible.

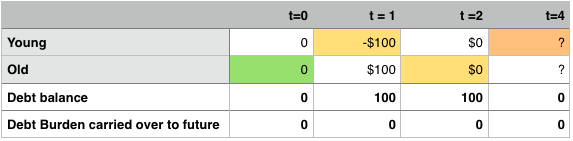

There are two generations (which are simplified into two people) alive in each time period, the ‘old’ and ‘young’. Each lives for two time periods, being young in their first time period, and old in their second. In the table below, which I will use to explain this, the coloured (and white) shaded cells are the same people, or cohort.

Starting from a no debt baseline at period zero, the first period has the old borrow $100 from the young. It doesn’t real matter whether this a new money (how we think of bank debts), direct peer-to-peer transfers, or taxes and welfare spending, the net effect is that those who borrow are able to capture a share of resources in that period.

In resource terms the young transfer $100 of resources to the old. In period two the previous old generation has died, and the previous young generation is now the old generation (yellow table cells), and there is a newly born young generation (white table cells).

The new young cohort then repays the debts, giving up $100 of resources to do so, which are transferred to the now old generation who lent the money in the previous period.

As Lerner explains, if you label the newly born young generation in period two as the ‘future generation’, which lives from period two to three (shaded white) and the cohort who originally borrowed the money in period one, who lived from period zero to one (also shaded white), the ‘present generation’, you can see how a transfer through time seems to occur.

The ‘present generation’ sees a lifetime consumption from debt of +$100, while the ‘future generation’ sees a total lifetime consumption of -$100 from this debt repayment.

Labelled in this way it seems perfectly obvious that debt burdens are being passed along. But only if we artificially conflate the creditor and debtors with 'generations', which can't be done in general.

But of course, the reality is that the resource transfers occur at each point in time, not between times. As the final row shows, in each period there is an accounting balance in resource terms between borrows and lenders. It is only because of the artificial way lenders and borrows are identified by generations, and the necessity to eliminate the debt balance in the next period that provides the result.

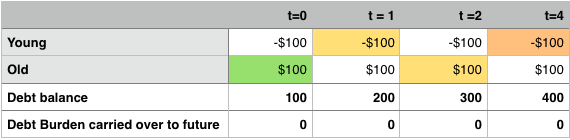

Let’s have a look at an alternative, where the same debt is incurred, but repaid (if at all) only after all generations alive upon its creation have died (and the real interest rate is zero for simplicity).

As you can see, this time it is clear that the generation born in the zero period is simply using debt to reallocate from the generation born in period one to themselves. Given the institutional power, they could of course have taxed that generation instead in order to redistribute resources. It is the same net effect.

The generational structure of the repayment of debt at some future point, however, is indeterminant. I have made this clear by labelling the period four repayment of debt with question marks, since who pays who in resource terms in that period for debt repayment is by its nature a result of all institutional resource allocations, including most importantly tax and transfer system. This is the general case.

A final illustration shows that when we consider continual debt-financed redistribution, that the redistribution problem goes away entirely, since all people receive the same redistributions at the same stages of their life. The table below show a continually debt funded reallocation from young to old, with ever increasing debt levels, but no identifiable winning or losing generation.

If you are concerned about general welfare of all people living at any point in time, then you must consider debts as internal transfers at a point in time.

Before I conclude this section, I need to again be clear that identifying winners and losers from these internal debt transfers is not at as easy as bundling all debtors and creditors together and labelling them. The complex interactions of the complete system of internal transfers means we simply cannot isolate these two groups. In fact, it may be very possible if an individual to be a borrower and lender at any point in time.

If I have just borrowed money to buy a house I am a borrower of purchasing power, which is paid for by the community at large via inflation and taxation. But of course I too am part of the community and give up resources via inflation and taxation. Understanding the balance even at an individual level is nigh impossible.

For a policy maker the whole system of transfers in a given period is all that matters, whether this occurs via taxation, transfers, debts or inflation. This is exactly what the core of macro economics says - debts are transfers in resource terms, and therefore balance out in aggregate. But somehow this is easily forgotten when it comes time to talk about policy.

Levels vs rates of change

The level of debt within an aggregate is not systematically important in terms of investment and macro economics. It is, however, important in terms of internal distribution, of which it forms a small component.

But the way in which debt levels change over time is vitally important to understanding the investment and business cycle. The reason being that debts in the private sector are typically incurred in order to finance new capital equipment and construction. By the nature of our banking and financial system, the rate of change in lending is a very good indicator of the aggregate investment occurring in the economy.

Steve Keen has repeatedly made the point is that rate of change in private debt, and its derivative (which he call acceleration of debt, being the second derivative of the debt level with respect to time), are far better indicators of the direction of the macro economics.

So while debt is an internal allocation, because our banking system generally produces debt in order to finance real new capital investment, the rate of change in the debt level can be used to understand the level of economic activity in aggregate.

This point is very subtle, but important. There is no conflict between the view that ones can look through debt in terms of its role in static allocations of resources, while at the same time understand debt dynamics as important mechanisms for financing new investment and therefore determining aggregate demand and growth.

Sadly, some economics tribal leaders have failed to acknowledge these subtleties and merely prefer to fight each other over confusing interpretations of what can be consistent ideas about debt.

Foreign debt

Finally, the mainstream economics tribe usually has divergent opinions about different forms of debt. Foreign debt gets relabelled as foreign investment and miraculously becomes a great thing. But of course this is the only type of debt where a country in aggregate is borrowing externally.

It is the type of debt most loved by economists in general, but the only one in which countries like Australia are generating future obligations to an external party.

The same rationale as before applies to foreign debts - the distribute role of levels versus the investment role of debt dynamics. Foreign debts are a resource transfer at a point in time. We can only accumulate foreign debts by running a deficit in the current account, typically by importing more goods than we export. Hence, in resource terms, we get the transfer from our imported resources.

The investment role here is far more subtle, because unlike domestic lending, there is not necessarily a close relationship between the creation of debts and new capital investment. But I won’t unpick this point any further in this post.

The point I want to make is that unlike internal debts, international debt balances are much more politically interesting. The two (in fact many) parties have different objectives, institutional constraints, and a complex web of non-monetary relationships such as military alliances, and resource interdependencies, such as reliance on either food or minerals imports.

Any questions about external debt are therefore inherently political.

One could construct a hypothetical baseline with which to compare and make judgements about external debts. This baseline would have a hypothetical market generate a relative currency value at a level that maintains a current account (and therefore capital account) balance. We only trade goods for goods in this scenario. In fact, it is a ‘no foreign debt’ scenario.

What we then need to determine is what benefits a country gains by deviating from this baseline over an extended period. We know that depressing a currency increases foreign demand for tradable goods, and therefore enables more rapid large scale investments in these sectors if there is sufficient internal organisation.

This has been a recipe for development in East Asia for the past many decades, and the subject of much political discussion and intervention (eg. the Plaza and Louvre Accords).

On the other side of the baseline we have countries like Australia that have run trade deficits and current account deficits in general for half a century. The benefits to such countries are short term gifts of relatively cheap tradable goods, at the cost of long term investment in those sectors.

Over time foreign debts have the surprising effects of generating greater reliance on each party for continued stability. In Europe we can see that ignorance of this fact is bringing down the area as a whole.

It should be obvious to any economist who understands their theoretical apparatus that the very existence of foreign debt is a sign of a political will on both sides to sustain an imbalance for their own national objectives. There is no need to continue looking at residual measures of productivity or technology or other magical explanations to understand what is ultimately a political construct.

Conclusions

Debt is a fundamental accounting feature of the monetary system. Economists used to know that they ‘looked through’ these accounts at real resources, and hence were able to see debts as merely the consequence of an internal reallocation. This lead most to believe that debt balances and their dynamics were of no interest at all.

Unfortunately, the discipline has seen a decline in the understanding of core concepts and theories, which I put down to a greater emphasis on a narrow set of mathematical techniques instead of their economic application and interpretation.

Yet there is a clear consistency between looking through debt levels as merely an account of past distributive choices, and paying very close attention to the dynamics of debt in relation to investment decisions, aggregate demand, asset prices and economic growth. Because private debts (and a portion of public debts) are, by the nature of lending processes, used for investment, their dynamics are both a signal of demand, and a driver of demand via feedbacks in the economy.

The inability to see this obvious consistency I believe is brought about by the perverse incentives in the discipline and its sociology that rewards loyalty to a tribe, and punishes attempts at reconciliation between tribes.

Currently there is much concern worldwide about debt. It is widely claimed that the mainstream economic community could not see a crisis coming because it fundamentally ‘looked through’ money and debt to the real economy. And since debt, or in fact the dynamics of debt, seemed an important factors in the crisis, this was a failure of the theory.

It is easy to agree with this critique. But to really understand it we have to disentangle all parts of it, and as we will see, there is an obvious way to reconcile the mainstream with the critique.

Household example

To begin, a theory of resource allocation is right to treat debt as an internal allocation mechanism of real resources in the economy.

In a my household, for example, I can lend my wife money to treat herself a new dress today. If we were accurately keeping internal household accounts that would be a transfer from myself to her. In real terms, my consumption of resources decreases and hers increases.

Next week the debt is ‘repaid’ according to our internal accounts when my wife lends me money to take the kids to the football.

When we look at our household as an aggregate entity, our total resource consumption is unchanged by the debt, which merely represents an internal reallocation.

There were no future resources brought forward for my wife to consume. The debt did not leave a cost to our children. Even if it was never repaid, I already paid for my household’s debt with the resources I didn’t consume when I transferred purchasing power to my wife.

It surprises me that on this crucial point the core mainstream concepts are consistent with the functional finance or modern monetary theory perspective, yet there remains animosity between these groups. I have come to believe that this is mostly a result of inadequate understanding of their own conceptual apparatus by the mainstream (here’s an example of how the noisiest mainstream commentators remain confused about their own theories).

Much of the mainstream has equated 'looking through' debt to the real resources of the economic with ignoring the money creation aspect of debt altogether. This has lead to further confusion in the analysis of banking and economics generally, with the Bank of England recently having to explain the process to the economics community.

These core economic concepts are easily confused when one fails to properly understand the complete accounting of the system at all points in time. Specifically the use of overlapping generations (OLG) models can confuse more than inform, and many students come away from learning these models believing in the possibility of inter-temporal reallocations of resources.

OLG example

To labour the point, the errors made in understanding the concepts at play in debt are evident in the overlapping generations models (OLG) which is commonly applied in economics in order to understand various internal shifts in resource burdens. It can be easily misunderstood to show that debt enables resources to travel through time.

Abba Lerner made the argument I am about to make back in 1961, when he was President of the American Economic Association. He was pulling into line economists Thomas Bowen, James Buchanan, and others, on their acceptance of the political propaganda that debt can distribute burdens across time. You’ve all heard a politician claim that debts are ‘leaving a burden for our children’.

The mistake of Bowen and Buchanan arises because of their incoherent conceptual application of the OLG model. In the model they merely redefine the current generation to mean those who lend the money, and the future generation as the one who pays the money (principle and interest) back.

Let me try and represent the model as simply as possible.

There are two generations (which are simplified into two people) alive in each time period, the ‘old’ and ‘young’. Each lives for two time periods, being young in their first time period, and old in their second. In the table below, which I will use to explain this, the coloured (and white) shaded cells are the same people, or cohort.

Starting from a no debt baseline at period zero, the first period has the old borrow $100 from the young. It doesn’t real matter whether this a new money (how we think of bank debts), direct peer-to-peer transfers, or taxes and welfare spending, the net effect is that those who borrow are able to capture a share of resources in that period.

In resource terms the young transfer $100 of resources to the old. In period two the previous old generation has died, and the previous young generation is now the old generation (yellow table cells), and there is a newly born young generation (white table cells).

The new young cohort then repays the debts, giving up $100 of resources to do so, which are transferred to the now old generation who lent the money in the previous period.

As Lerner explains, if you label the newly born young generation in period two as the ‘future generation’, which lives from period two to three (shaded white) and the cohort who originally borrowed the money in period one, who lived from period zero to one (also shaded white), the ‘present generation’, you can see how a transfer through time seems to occur.

The ‘present generation’ sees a lifetime consumption from debt of +$100, while the ‘future generation’ sees a total lifetime consumption of -$100 from this debt repayment.

Labelled in this way it seems perfectly obvious that debt burdens are being passed along. But only if we artificially conflate the creditor and debtors with 'generations', which can't be done in general.

But of course, the reality is that the resource transfers occur at each point in time, not between times. As the final row shows, in each period there is an accounting balance in resource terms between borrows and lenders. It is only because of the artificial way lenders and borrows are identified by generations, and the necessity to eliminate the debt balance in the next period that provides the result.

Let’s have a look at an alternative, where the same debt is incurred, but repaid (if at all) only after all generations alive upon its creation have died (and the real interest rate is zero for simplicity).

The generational structure of the repayment of debt at some future point, however, is indeterminant. I have made this clear by labelling the period four repayment of debt with question marks, since who pays who in resource terms in that period for debt repayment is by its nature a result of all institutional resource allocations, including most importantly tax and transfer system. This is the general case.

A final illustration shows that when we consider continual debt-financed redistribution, that the redistribution problem goes away entirely, since all people receive the same redistributions at the same stages of their life. The table below show a continually debt funded reallocation from young to old, with ever increasing debt levels, but no identifiable winning or losing generation.

If you are concerned about general welfare of all people living at any point in time, then you must consider debts as internal transfers at a point in time.

Before I conclude this section, I need to again be clear that identifying winners and losers from these internal debt transfers is not at as easy as bundling all debtors and creditors together and labelling them. The complex interactions of the complete system of internal transfers means we simply cannot isolate these two groups. In fact, it may be very possible if an individual to be a borrower and lender at any point in time.

If I have just borrowed money to buy a house I am a borrower of purchasing power, which is paid for by the community at large via inflation and taxation. But of course I too am part of the community and give up resources via inflation and taxation. Understanding the balance even at an individual level is nigh impossible.

For a policy maker the whole system of transfers in a given period is all that matters, whether this occurs via taxation, transfers, debts or inflation. This is exactly what the core of macro economics says - debts are transfers in resource terms, and therefore balance out in aggregate. But somehow this is easily forgotten when it comes time to talk about policy.

Levels vs rates of change

The level of debt within an aggregate is not systematically important in terms of investment and macro economics. It is, however, important in terms of internal distribution, of which it forms a small component.

But the way in which debt levels change over time is vitally important to understanding the investment and business cycle. The reason being that debts in the private sector are typically incurred in order to finance new capital equipment and construction. By the nature of our banking and financial system, the rate of change in lending is a very good indicator of the aggregate investment occurring in the economy.

Steve Keen has repeatedly made the point is that rate of change in private debt, and its derivative (which he call acceleration of debt, being the second derivative of the debt level with respect to time), are far better indicators of the direction of the macro economics.

So while debt is an internal allocation, because our banking system generally produces debt in order to finance real new capital investment, the rate of change in the debt level can be used to understand the level of economic activity in aggregate.

This point is very subtle, but important. There is no conflict between the view that ones can look through debt in terms of its role in static allocations of resources, while at the same time understand debt dynamics as important mechanisms for financing new investment and therefore determining aggregate demand and growth.

Sadly, some economics tribal leaders have failed to acknowledge these subtleties and merely prefer to fight each other over confusing interpretations of what can be consistent ideas about debt.

Foreign debt

Finally, the mainstream economics tribe usually has divergent opinions about different forms of debt. Foreign debt gets relabelled as foreign investment and miraculously becomes a great thing. But of course this is the only type of debt where a country in aggregate is borrowing externally.

It is the type of debt most loved by economists in general, but the only one in which countries like Australia are generating future obligations to an external party.

The same rationale as before applies to foreign debts - the distribute role of levels versus the investment role of debt dynamics. Foreign debts are a resource transfer at a point in time. We can only accumulate foreign debts by running a deficit in the current account, typically by importing more goods than we export. Hence, in resource terms, we get the transfer from our imported resources.

The investment role here is far more subtle, because unlike domestic lending, there is not necessarily a close relationship between the creation of debts and new capital investment. But I won’t unpick this point any further in this post.

The point I want to make is that unlike internal debts, international debt balances are much more politically interesting. The two (in fact many) parties have different objectives, institutional constraints, and a complex web of non-monetary relationships such as military alliances, and resource interdependencies, such as reliance on either food or minerals imports.

Any questions about external debt are therefore inherently political.

One could construct a hypothetical baseline with which to compare and make judgements about external debts. This baseline would have a hypothetical market generate a relative currency value at a level that maintains a current account (and therefore capital account) balance. We only trade goods for goods in this scenario. In fact, it is a ‘no foreign debt’ scenario.

What we then need to determine is what benefits a country gains by deviating from this baseline over an extended period. We know that depressing a currency increases foreign demand for tradable goods, and therefore enables more rapid large scale investments in these sectors if there is sufficient internal organisation.

This has been a recipe for development in East Asia for the past many decades, and the subject of much political discussion and intervention (eg. the Plaza and Louvre Accords).

On the other side of the baseline we have countries like Australia that have run trade deficits and current account deficits in general for half a century. The benefits to such countries are short term gifts of relatively cheap tradable goods, at the cost of long term investment in those sectors.

Over time foreign debts have the surprising effects of generating greater reliance on each party for continued stability. In Europe we can see that ignorance of this fact is bringing down the area as a whole.

It should be obvious to any economist who understands their theoretical apparatus that the very existence of foreign debt is a sign of a political will on both sides to sustain an imbalance for their own national objectives. There is no need to continue looking at residual measures of productivity or technology or other magical explanations to understand what is ultimately a political construct.

Conclusions

Debt is a fundamental accounting feature of the monetary system. Economists used to know that they ‘looked through’ these accounts at real resources, and hence were able to see debts as merely the consequence of an internal reallocation. This lead most to believe that debt balances and their dynamics were of no interest at all.

Unfortunately, the discipline has seen a decline in the understanding of core concepts and theories, which I put down to a greater emphasis on a narrow set of mathematical techniques instead of their economic application and interpretation.

Yet there is a clear consistency between looking through debt levels as merely an account of past distributive choices, and paying very close attention to the dynamics of debt in relation to investment decisions, aggregate demand, asset prices and economic growth. Because private debts (and a portion of public debts) are, by the nature of lending processes, used for investment, their dynamics are both a signal of demand, and a driver of demand via feedbacks in the economy.

The inability to see this obvious consistency I believe is brought about by the perverse incentives in the discipline and its sociology that rewards loyalty to a tribe, and punishes attempts at reconciliation between tribes.