Monday, October 4, 2010

Statistics lessons for property people

In a recent bulletin to members he criticised the Local Government Association of Queensland’s interpretation of a report they commissioned on factors affecting home prices in South East Queensland.

He questions the conclusion that the AEC report commissioned by LGAQ refutes ‘for all time the spurious arguments of a so-called under-supply of dwellings in the SEQ market’. If he had paid attention in statistics it would be clear to him that this is exactly what the report does.

Although the report is far from an exemplary analysis of key determinants of residential property prices, the authors did estimate six econometric models to seek the determinants of real median house, unit and land prices in SEQ - eighteen models in total. If we quickly browse the report we find just one model, for house prices, not unit or land prices, where any of their supply-side variables is significant in explain real prices.

To be sure, Stewart’s interpretation of the report was poor, and his bulletin misleading, but I still have reservations about the report itself.

Particularly I have concerns about the choice of, and construction of, variables, including location bias in calculating the median prices and using ratios to total stock rather than sales volumes (particularly in the treatment of the FHOG). It seems odd that with 69 data points and 32 variables at hand they had trouble finding significant relationships in the data – could it be their selection was stacked with the wrong variables to explain prices?

One example of the construction of variable is ‘SEQ housing stock per capita’, which is total stock for SEQ at the beginning of the period at the beginning of the analysis (1991) of 734,126, less an allowance for depreciation (about 0.3%), plus new stock completed IN QUEENSLAND in the period. This variable then accumulates over time to represent the stock of housing.

I first hope that the new stock only includes new stock in the SEQ region and that this is a typo. Second, I can’t see how depreciating a dwelling is good accounting. What should be considered is a factor for demolitions, and it would be easy enough to estimate the demolition to new dwelling ratio based on past census data.

These types of errors abound.

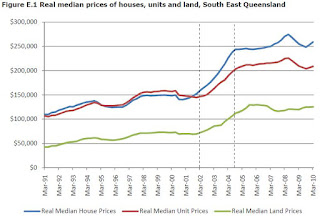

Most importantly I wonder how this controversial variable could be negatively correlated with prices. In the section on housing stock (p13) it shows that dwelling stock per 100 people grew from 38.1 to 41.1 from 1991 to 2006, while real prices grew from around $100,000 to $250,000 in this period (below). Either a) the three other significant variables, the All Ordinaries, unemployment and mortgage rates, explained the most of the change, or b) the variable used in the analysis is the CHANGE IN dwelling stock per person, which was positive but declining over the period.

What is further surprising is the conclusion that the SEQ property market somehow behaves differently to other parts of the country. Given that the analysis failed to explain the behaviour of the SEQ residential property market at all (their final land price model on page 29 had seven variables but just two were significant), one wonders how such conclusions are drawn. I am happy for someone to explain why it is different here (cringe) if they have the evidence to support the statement.

Anyone looking to elastify the supply side should note the report concludes by noting how responsive supply has in fact been to prices:

...the lot stock for SEQ rose from 25,000 during the early part of the decade to reach 50,000 by December 2005 and has stabilised around 54,000 since September 2007. This progression follows the growth in land prices very closely, indicating that supply of undeveloped residential lots has responded to price signals.

Thursday, September 30, 2010

Common sense and the CityCycle launch

Monday, September 27, 2010

Too good to be true environmental solutions

Sunday, September 26, 2010

Lessons for the RBA on their blunt instrument

... we only have one set of interest rates for the whole Australian economy; we do not have different interest rates for certain regions or industries. We set policy for the average Australian conditions. A given region or industry may not fully feel the strength or weakness in the overall economy to which the Bank is responding with monetary policy. In fact no region or industry may be having exactly the ‘average’ experience. It is this phenomenon that people presumably have in mind when they refer to monetary policy being a ‘blunt instrument.

I think poor old Glenn is taking his hammer to a screw.

While he wisely notes we have one set of interest rates, not one interest rate, he seems to ignore the fact that differentiation of interest rates on debt should reflect the risk for each particular loan. The problem for the RBA is that those who actually lend in the marketplace are failing to properly price the risk premium associated with their particular loans. Housing is surely a risky investment at the moment, yet interest rates do not reflect the risk premium.

The obvious alternative to shifting the whole set of interest rates is to better manage the risk premium rate for a particular industry of concern, or forcefully adjust risks taken with other measures to suit the rates adopted in that industry.

For example, if banks insist on lending for housing at relatively low interest rates, they can reduce risk by keeping lower LVRs and more conservative income estimates. If they won’t do it voluntarily, because they suffer from extreme moral hazard associated with guaranteed government bail-outs, maybe the RBA can seek to have banks better regulated with regards to housing loan risks, particularly qualifying income and LVRs.

At the moment increasing interest rates will simple increase the interest burden on current debts, high risk or not, decrease take up of borrowing for productive purposes, and fail to curb the mispricing of risk and crude lending criteria of housing loans with the major banks.

Thursday, September 23, 2010

What I have found interesting lately

Tuesday, September 21, 2010

Gaming leads to unintended consequences when governments try to stimulate housing supply

The aggressiveness of changes to planning instruments to allow for greater heights and densities, and allow fringe areas into the urban footprint, provided opportunities to profit simply from speculation on the next change to the planning scheme. For landowners it became more profitable to wait three years for the local government to update the planning scheme to allow greater density of development, than to actually develop the site.

One example, South Brisbane, epitomises this situation.

At this prime location, within a stone's throw of the CBD, the previous limits of 12 and eight storeys were already conservative.The planning scheme for this precinct has changed from allowing four storeys, to seven storeys, then proposing eight storeys, then twelve storeys in the latest draft plan, and now the UDIA is calling to increase the heights much further. With the approval of a 30-storey tower adjacent to Milton railway station, one could assume there is a long way to go in this saga.

Expectations were for this pattern to continue. A landholder in this area recently mentioned they have no reason to sell or develop when the council keeps increasing the value of their land by changing the planning scheme. Landholders are gaming the Council, waiting for a signal that the gifts will soon expire before selling up to developers.

Maybe that signal is here.

The State government has intervened in the latest round of planning scheme changes to request the proposed height limits be cut back – where 12 storeys was proposed, they will allow seven.

For anyone aware of the standoff taking place the flood of development sites onto the market in the month since the State government decision would come as no surprise. Who would have thought reducing height limits would promote so much development activity?

The moral of this story is that certainty (or lack thereof) can greatly change real outcomes. Economists often foolishly assume that all government decisions are taken at face value by the marketplace. Few realise the time element and that parties affected will already be anticipating the next decision, or gambling on a political backflip.

UPDATE: More evidence of rewarding land banking rather than productive land use, from the Local Government Association of Queensland -

The LGAQ today criticised a key provision of legislation introduced to state parliament on Tuesday which retained a 40 per cent rate subsidy for large companies holding big tracts of land approved for development but not yet formally subdivided.

The money at stake is not the issue here. The issue is the massive contradiction of rewarding developers for not sub-dividing land to increase supply when the state government says it is championing housing affordability issues

Sunday, September 19, 2010

Flow-on effects of recycling - are there net benefits?

Like efficiency, the word recycling reflects positivity from all angles. How could anyone say a bad thing about recycling?

I propose not to say a bad thing for the sake of cementing my identity as a super-sceptic, but to examine in detail the potential flow-on effects of recycling and determine whether the espoused benefits can theoretically be delivered.

Generally two benefits of recycling are proclaimed. First, waste will be diverted from landfill, thus we can reduce the space required for this purposed and reduce the threat of leaching from landfill sites into groundwater systems and other environments. Second, recycled material will substitute for raw materials and thus reduce consumption of natural resources which may have associated negative environmental externalities.

These are two distinct benefits, and achieving one does not necessarily imply achieving both.

There are also two different economic scenarios for achieving recycling with different outcomes – the profitable recycling scenario, and the unprofitable recycling scenario that requires government support.

The profitable scenario represents an improvement in overall economic efficiency, thus, like the case of profitable energy efficiency, it facilitates future economic growth and improves our productive capacity.

In this scenario, recycled material cannot be said to be diverted from land fill, because it would never have been put there in the first place due to the material’s value to remanufacturing. If the material was simply dumped on the street there would be an opportunity for a business to emerge to collect the material and sell for a profit. Without a counterfactual we cannot estimate the effect on either of our two recycling claims.

If we assume instead that the counterfactual scenario is one where the technology had not yet emerged to make recycling profitable, then we can now consider the flow-on effects from the technology. It is best to have a single material in mind, say glass, when thinking of these effects.

First, the price of the final goods (windows, bottles etc) using the newly recyclable material will decline due to the reduced cost of recycled instead of raw materials. Thus we will see an increase in demand (not a shift in the demand curve, but a new point on the demand curve at a lower price) for these final goods and therefore an increase in demand for recycled and/or raw materials (recycled glass or silica from natural sand deposits). Depending on the availability of recycled material compared to the total quantity of raw materials, this can lead to greater demand for natural resource itself (sand mining).

We can now say we have probably diverted waste from landfill leading to a greater quantity of material circulating in the hands of society (as either capital equipment – glass in buildings perhaps- or soon to be recycled consumables – maybe bottles), but we cannot say with certainty that the new recycling technology has reduced demand for the particular natural resource in question. Nor can we say that demand for, and consumption of, other natural resources remains unaffected. In fact the new recycling technology, since it improved overall economic efficiency, is likely to increase demand for all natural resource inputs to the economy.

The alternate unprofitable scenario represents a decrease in overall economic efficiency, and will reduce overall economic activity compared to scenario where government did not use its coercive power to enforce this unprofitable venture.

In this scenario we are likely to see a decline in waste to landfill compared to the economically efficient situation where recycling is not subsidised. We face the same situation of compensatory demand due to price declines of final goods manufactured using the cheaper subsidised recycled materials. This scale of this offsetting behaviour cannot be readily estimated and is likely to strongly depend on the relative prices and quantities of the recycled materials and raw material inputs are a particular point in time. A decline in overall demand for raw materials in the economy as a whole is certain in the unprofitable scenario due to the overall reduction in economic efficiency.

For unprofitable recycling the net result will be a reduction in waste to landfill of both the recycled good and other goods (since we can now produce fewer goods in total across the economy), and a reduction in resource consumption of the recycled material and all other resource inputs to the economy.

In what is becoming a familiar environmental theme at this blog, it should be clear that indirect measures to curb negative environmental impacts from our activities, such as promoting conservation behaviours, profitable energy efficiency, and recycling, have questionable net impacts on the environmental issue at hand.

Returning to our two main environmental goals of recycling – reduce negative impacts form landfill sites and reduce resource extraction that involves an environmental burden – we can clearly offer more direct measures which are both easy to establish and have certain environmental benefits.

The first environmental goal can be achieved by setting minimum environmental standards for landfill sites to address leaching (or any other associated problem depending on local conditions) including, perhaps, restrictions on location. In response to these criteria, landfill operators (public or private) would need to adopt appropriate measure to limit external impacts – possibly lining their pits with impermeable material, sorting, washing or removing particular types of waste, or some other creative response. These extra costs of waste disposal – the internalised environmental cost – will flow through to the cost of disposal, and may render some recycling programs profitable.

For the second environmental concern, resource extraction, similar direct controls can be used. Sticking with the glass example, the scope of sand mining can be limited through planning controls where natural environments which are valued by the community. Once this limit is established, sand mining in that area can proceed, at any particular rate, with certainty that there is a finite limit to the environmental cost.

These limits would never be, strictly speaking, perfect. They would at best reflect the perceived value of the environment to the community. There is no reason that the limits should not be stricter in some areas than others.

As an indirect environmental measure with questionable benefits, recycling, like efficiency, is claimed to be a panacea for a variety of poorly defined environmental ills. We often forget to critically examine the link between this indirect environmental ‘remedy’, and the target environmental illness.

Friday, September 17, 2010

A closer look at Australian incomes and predictions from Google Trends

Tuesday, September 14, 2010

Energy efficiency - further reading

Brookes also adds taxing resources to reflect the cost of negative externalities, which one assumes, would be spent on reparation activities to return to a new optimal resource allocation which internalises the cost of pollution and eliminates the possibility of rebound effects (if reparations are possible).

It is worth reading his conclusions in full (below the fold):

Sunday, September 12, 2010

Dutch Cargo Bike Review

Note: A follow-up (3yr) review is here. I am now a local ambassador for Dutch Cargo Bikes. If you would like to test rise this bike in Brisbane (or a three wheeler) email me at cameron@dutchcargobike.com.auI almost convinced myself not long ago that a bicycle for carrying children was a completely unjustified expense. Luckily I didn't. Because my sparkling new bakfiets.nl cargo bike, supplied through Dutch Cargo Bike, arrived several weeks ago. And I'm excited. I've also convinced myself that in reality it isn't expensive, and in fact represents great value for money.

fn.[1] The alert reader will note there is an opportunity cost to the forgone $3000 that could have been alternatively invested, say at 5%, which adds another $150 per year.