Saw this advertisement today in the Financial Review. I haven't seen anything like it before but it reeks of desperation. Is it some kind of joke?

I like the first part of the fine print "Real Estate agents tell me I can get $2.1million for my luxury home but..."

Showing posts with label Housing market. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Housing market. Show all posts

Thursday, May 5, 2011

Wednesday, May 4, 2011

Housing stimulus idea

From Crikey:

Local bike paths mean higher house prices

That is one housing stimulus package I would be happy to see implemented. From the comments section:

More accurate take on alternate headline –

Bikeways found to be desirable trait amongst urban home buyers.

Temporary shortage of bikeways elevates prices in areas with bike paths.

Once all areas have bike paths, price distortion will be nil.

Captain Planet

Local bike paths mean higher house prices

That is one housing stimulus package I would be happy to see implemented. From the comments section:

More accurate take on alternate headline –

Bikeways found to be desirable trait amongst urban home buyers.

Temporary shortage of bikeways elevates prices in areas with bike paths.

Once all areas have bike paths, price distortion will be nil.

Captain Planet

Demand shocks – the details

Many pundits claim that increasing population increases demand. In technical economic jargon it shifts the curve to the right. But what we rarely see is an exploration of the two types of demand shock and the different potential price impacts.

The first type, as mentioned above, shifts the downward sloping demand curve to the right. This means there are more people with the same willingness to pay.

The second type is a shift of the demand curve up upwards. This represents a willingness to pay more for the same goods from the same number of people.

It’s pretty clear from this distinction which of these factors is in play in Australian housing.

Let’s examine the first case. Consider an auction with 10 cars for sale and 50 bidders willing to pay $1000 for a car. You add another 50 people to the mix each also willing to pay $1000. If I’m not being clear enough, this is analogous to increasing population in the housing context.

When the auction is run with the original 50 bidders each car sells for $1,000. When the auction is run with 100 bidders, the 10 cars still sell for $1,000 each.

This is an extreme scenario but does demonstrate a very real point. Unless the new potential buyers are willing to pay more for the same items as the existing buyers, the price won’t rise. At most, a second price auction (the result of an English open auction with heterogeneous preferences) becomes closer to a first price sealed bid auction by the addition of another bidder willing to bid at a price between the second and first price (read up on some auction theory here).

As I said before, new buyers, even a small cohort of the total market, can influence the price level if they are willing to pay more than the existing buyers, since prices are set at the margins. Imagine our car auction once again, and we give 10 of our original 50 bidders and extra $500 to spend on the car. What is the new result? All cars sell for $1500 each to these 10 bidders. Even though they were just 20% of the original market of buyers, they dragged the price up 50%. In fact even if there were thousands of buyers willing and able to pay $1000 for those 10 cars, the ten people willing to pay $1500 would always win.

Prices are set at the margin by those with the highest willingness to pay.

This example, where the demand curve is shifted vertically to reflect an increased willingness to pay by the same number of buyers, is shown graphically in the right hand side graph above.

But, you say, the key problem here is that supply is being overlooked - in the simplified examples demand curves are horizontal and there is no supply response. But look at the graphs again. Not only is the demand curve a more acceptable shape, but supply does respond in both circumstances. In the first, where the demand profile of buyers shifts horizontally supply does respond enabling prices to remain at their equilibrium level.

However, when the demand curve shifts vertically, it doesn’t matter how much supply responds to price increases, it cannot be a mechanism to bring prices back down (except under extreme assumptions about the shape of demand and supply and the limits of peoples willingness to pay at the top and bottom of the market).

Of course, in the end this analysis is probably unecessary. The value of housing arises from the rents - its ability to generate revenue or provide a service. Since we haven’t seen rents outpace inflation significantly for any extended period in the past two decades, one must be quite certain that the cause of prices being much higher than a rational present value of future cash flows is pure demand side speculation.

The first type, as mentioned above, shifts the downward sloping demand curve to the right. This means there are more people with the same willingness to pay.

The second type is a shift of the demand curve up upwards. This represents a willingness to pay more for the same goods from the same number of people.

It’s pretty clear from this distinction which of these factors is in play in Australian housing.

Let’s examine the first case. Consider an auction with 10 cars for sale and 50 bidders willing to pay $1000 for a car. You add another 50 people to the mix each also willing to pay $1000. If I’m not being clear enough, this is analogous to increasing population in the housing context.

When the auction is run with the original 50 bidders each car sells for $1,000. When the auction is run with 100 bidders, the 10 cars still sell for $1,000 each.

This is an extreme scenario but does demonstrate a very real point. Unless the new potential buyers are willing to pay more for the same items as the existing buyers, the price won’t rise. At most, a second price auction (the result of an English open auction with heterogeneous preferences) becomes closer to a first price sealed bid auction by the addition of another bidder willing to bid at a price between the second and first price (read up on some auction theory here).

As I said before, new buyers, even a small cohort of the total market, can influence the price level if they are willing to pay more than the existing buyers, since prices are set at the margins. Imagine our car auction once again, and we give 10 of our original 50 bidders and extra $500 to spend on the car. What is the new result? All cars sell for $1500 each to these 10 bidders. Even though they were just 20% of the original market of buyers, they dragged the price up 50%. In fact even if there were thousands of buyers willing and able to pay $1000 for those 10 cars, the ten people willing to pay $1500 would always win.

Prices are set at the margin by those with the highest willingness to pay.

This example, where the demand curve is shifted vertically to reflect an increased willingness to pay by the same number of buyers, is shown graphically in the right hand side graph above.

But, you say, the key problem here is that supply is being overlooked - in the simplified examples demand curves are horizontal and there is no supply response. But look at the graphs again. Not only is the demand curve a more acceptable shape, but supply does respond in both circumstances. In the first, where the demand profile of buyers shifts horizontally supply does respond enabling prices to remain at their equilibrium level.

However, when the demand curve shifts vertically, it doesn’t matter how much supply responds to price increases, it cannot be a mechanism to bring prices back down (except under extreme assumptions about the shape of demand and supply and the limits of peoples willingness to pay at the top and bottom of the market).

Of course, in the end this analysis is probably unecessary. The value of housing arises from the rents - its ability to generate revenue or provide a service. Since we haven’t seen rents outpace inflation significantly for any extended period in the past two decades, one must be quite certain that the cause of prices being much higher than a rational present value of future cash flows is pure demand side speculation.

Economics, Real Estate and the Supply of Land

As a general rule, economists relying on supply and demand curves without properly discussing the assumptions that sit underneath their graphs can be ignored.

Alan Evans' book Economics, Real Estate and the Supply of Land is an effort to refute Ricardian notions of land supply and rent, and offer an alternative neoclassical theory of land supply. The arguments in this book are taken by many who believe that reducing government involvement in town planning will decrease the price of housing. Evans’ reasoning is questionable to say the least, and supported by elaborate graphs with often biased assumptions and interpretations.

One of Evans’ aims is to refute the Ricardian proposition ‘that the price of land is high because the price of corn [read: houses] is high, and not vice versa’.

To do this he constructs a model economy with a fixed land supply where two agricultural uses compete for land – potatoes and corn. In the figure below we see his construction of this economy on the left, with demand for corn inverted so that the intersection of corn and potato demand determines the equilibrium share of land devoted to each crop, and the equilibrium rent of land at point A.

He then proceeds to add a demand shock to potatoes ‘for some reason’. The new blue line represents the new increased demand for potatoes which enables potato growers to bid up prices for land previously grown for corn and reduce the amount of land used to grow corn. He concludes with the following -

Now it is quite clear that the increase in the rent of land is not caused by the increase in the price of corn. Exactly the reverse is true. The price of corn has risen because the price of land has risen.

...

The rent for land is not solely determined by the demand for the product.

His conclusions are wrong.

First, it is still quite clear that at the new equilibrium the price of land for corn is still determined by the new higher price for corn. You could just as easily argue that every time a potato grower buys land from a corn grower he decreases the output of corn and the price of corn rises, thereby leading to an increase in the rents of land available for growing corn.

Second, he fails to notice that all he has done with the model is to demonstrate the inflation mechanism following an increase in money supply for one purpose. He increases total demand (potatoes plus corn) but shifts preferences towards potatoes so that corn demand is constant. The end result of his demand increase is to increase all prices in the model economy – potatoes, corn and rent.

Followers of Say would jump straight to this conclusion. You can’t simply increase total demand in the economy – demand is comprised of supply.

An actual demand shock, which models a change in preferences from corn to potatoes, is shown in the right hand side figure. You will notice that total demand remains constant and therefore the rents for this fixed quantity of land also remain constant.

So no, land rents do not determine prices. Prices determine rents.

Another example of poor reasoning is when Evans argues against a 100% land value tax. He argues that a tax of that nature would ‘freeze’ land development because there would be no incentive for a owner of agricultural land to sell his land to a developer for housing development, since he would not capture any of the value uplift. The rent achieved by the owner of the land will remain the same as when it is rented to the farmer – zero.

Yet in chapter 8 he argues that the value of land grows in anticipation of future higher value uses. In these cases, when the site is genuinely worth more as housing, the tax would be at a rate that reflects that higher value, and not the agricultural value. Therefore, the owner of the land will be facing a tax on the land value for housing while only receiving rents at agricultural values. As the city expands and the value of his land for housing surpasses the value for agriculture, he has a great incentive to sell or develop immediately to avoid losses.

Although I don’t support a 100% land value tax, I do support shifting the tax burden towards land and fixed rights to natural resources.

What we do learn from this book is that even the experts are prone to bias that affects their ability to apply objective logic and reason.

Alan Evans' book Economics, Real Estate and the Supply of Land is an effort to refute Ricardian notions of land supply and rent, and offer an alternative neoclassical theory of land supply. The arguments in this book are taken by many who believe that reducing government involvement in town planning will decrease the price of housing. Evans’ reasoning is questionable to say the least, and supported by elaborate graphs with often biased assumptions and interpretations.

One of Evans’ aims is to refute the Ricardian proposition ‘that the price of land is high because the price of corn [read: houses] is high, and not vice versa’.

To do this he constructs a model economy with a fixed land supply where two agricultural uses compete for land – potatoes and corn. In the figure below we see his construction of this economy on the left, with demand for corn inverted so that the intersection of corn and potato demand determines the equilibrium share of land devoted to each crop, and the equilibrium rent of land at point A.

He then proceeds to add a demand shock to potatoes ‘for some reason’. The new blue line represents the new increased demand for potatoes which enables potato growers to bid up prices for land previously grown for corn and reduce the amount of land used to grow corn. He concludes with the following -

Now it is quite clear that the increase in the rent of land is not caused by the increase in the price of corn. Exactly the reverse is true. The price of corn has risen because the price of land has risen.

...

The rent for land is not solely determined by the demand for the product.

His conclusions are wrong.

First, it is still quite clear that at the new equilibrium the price of land for corn is still determined by the new higher price for corn. You could just as easily argue that every time a potato grower buys land from a corn grower he decreases the output of corn and the price of corn rises, thereby leading to an increase in the rents of land available for growing corn.

Second, he fails to notice that all he has done with the model is to demonstrate the inflation mechanism following an increase in money supply for one purpose. He increases total demand (potatoes plus corn) but shifts preferences towards potatoes so that corn demand is constant. The end result of his demand increase is to increase all prices in the model economy – potatoes, corn and rent.

Followers of Say would jump straight to this conclusion. You can’t simply increase total demand in the economy – demand is comprised of supply.

An actual demand shock, which models a change in preferences from corn to potatoes, is shown in the right hand side figure. You will notice that total demand remains constant and therefore the rents for this fixed quantity of land also remain constant.

So no, land rents do not determine prices. Prices determine rents.

Another example of poor reasoning is when Evans argues against a 100% land value tax. He argues that a tax of that nature would ‘freeze’ land development because there would be no incentive for a owner of agricultural land to sell his land to a developer for housing development, since he would not capture any of the value uplift. The rent achieved by the owner of the land will remain the same as when it is rented to the farmer – zero.

Yet in chapter 8 he argues that the value of land grows in anticipation of future higher value uses. In these cases, when the site is genuinely worth more as housing, the tax would be at a rate that reflects that higher value, and not the agricultural value. Therefore, the owner of the land will be facing a tax on the land value for housing while only receiving rents at agricultural values. As the city expands and the value of his land for housing surpasses the value for agriculture, he has a great incentive to sell or develop immediately to avoid losses.

Although I don’t support a 100% land value tax, I do support shifting the tax burden towards land and fixed rights to natural resources.

What we do learn from this book is that even the experts are prone to bias that affects their ability to apply objective logic and reason.

Thursday, April 28, 2011

Faulty Reasoning

I’ve come across some fine examples of faulty reasoning lately in two key areas.

1. Analysing the economic importance of declining environmental quality, and

2. Assessing the impact of price drops in the Australian property market.

So let us take a closer look.

Pro-urban sprawl advocates (I didn’t really know there were so many until just recently) try to shrug off the claim of deterimental impacts on agricultural production from urban sprawl due to irreversibly land use changes. For example –

Suburban Development is not destroying farmland. Smart growth activists claim farmland is disappearing at dangerous rates and that government needs to protect farmland lest we lose the ability to feed ourselves. As growth expert Julian Simon wrote, this claim is "the most conclusively discredited environmental-political fraud of recent times." United States Department of Agriculture data show that from 1945 to 1992 cropland area remained constant at 24 percent of the United States. Though urban land uses increased, they now account for only 3 percent of the land area of the United States. Today, American farmers produce more food per acre than ever before. In fact, the number of acres used for crops peaked in 1930, but because of the ingenuity and innovation of American farmers, the United States continues to produce more food on less land. (here)

Why is this argument based on faulty reasoning?

1. Analysing the economic importance of declining environmental quality, and

2. Assessing the impact of price drops in the Australian property market.

So let us take a closer look.

Pro-urban sprawl advocates (I didn’t really know there were so many until just recently) try to shrug off the claim of deterimental impacts on agricultural production from urban sprawl due to irreversibly land use changes. For example –

Suburban Development is not destroying farmland. Smart growth activists claim farmland is disappearing at dangerous rates and that government needs to protect farmland lest we lose the ability to feed ourselves. As growth expert Julian Simon wrote, this claim is "the most conclusively discredited environmental-political fraud of recent times." United States Department of Agriculture data show that from 1945 to 1992 cropland area remained constant at 24 percent of the United States. Though urban land uses increased, they now account for only 3 percent of the land area of the United States. Today, American farmers produce more food per acre than ever before. In fact, the number of acres used for crops peaked in 1930, but because of the ingenuity and innovation of American farmers, the United States continues to produce more food on less land. (here)

Why is this argument based on faulty reasoning?

Sunday, April 17, 2011

Housing supply follow up – more evidence (UPDATED)

I promised to search around for some more evidence that local councils approve far more dwellings than are built. This would go some way to addressing the argument than planning is restrict, particularly zoning controls and approvals processes.

This report, by the Queensland Office of Economic and Statistical Reseach, adds to the previous evidence on a deevlopment approvals for subdivisions greatly exceeding the ability of the market to absorb the new land. It outlines the number of development approvals for infill multiple unit dwellings in the pipeline at various stages of approval for South East Queensland.

The telling figure is that there are 48,152 approved new infill dwellings in SEQ, with another 29,014 at earlier stages of approval. Remembering that there are also 30,566 approved subdividede housing blocks, we have a total approved supply in this region of 88,718 dwellings! Even at its recent peak population growth in SEQ was only 88,000 per year. That makes about 2.5 years supply of dwellings already approved.

Other government reports which have compiled useful information on the potential housing supply available under current planning regimes.

This report notes the following

“...there appears to be a very low risk of the current broadhectare land not providing at least 15 years supply, particularly when the increased density and infill targets set by the SEQ Regional Plan are considered. Based on the SEQ Regional Plan assumptions for infill, then only 244,000 lots would be required over a fifteen year period”

Moreover it explains that the stock of approved lots represents 3.3 years supply.

We can take a look at a national level here and see that current planning schemes have the potential to yield 131,000 new homes per year for a decade from 2008! This excludes the increase in housing stock from developments with less than 10 dwellings. In the abovelinked OESR report they state that smaller developments of 10 or fewer dwellings accounted for 69.5 per cent of projects at June 2010. This means the estimate of 131,000 new homes accounts for only 40% of the actual supply available under current planning schemes.

Even so, they sum up their analysis of land supply by stating that there was approximately 7–8 years supply of zoned broadhectare land in 2007.

This report, by the Queensland Office of Economic and Statistical Reseach, adds to the previous evidence on a deevlopment approvals for subdivisions greatly exceeding the ability of the market to absorb the new land. It outlines the number of development approvals for infill multiple unit dwellings in the pipeline at various stages of approval for South East Queensland.

The telling figure is that there are 48,152 approved new infill dwellings in SEQ, with another 29,014 at earlier stages of approval. Remembering that there are also 30,566 approved subdividede housing blocks, we have a total approved supply in this region of 88,718 dwellings! Even at its recent peak population growth in SEQ was only 88,000 per year. That makes about 2.5 years supply of dwellings already approved.

Other government reports which have compiled useful information on the potential housing supply available under current planning regimes.

This report notes the following

“...there appears to be a very low risk of the current broadhectare land not providing at least 15 years supply, particularly when the increased density and infill targets set by the SEQ Regional Plan are considered. Based on the SEQ Regional Plan assumptions for infill, then only 244,000 lots would be required over a fifteen year period”

Moreover it explains that the stock of approved lots represents 3.3 years supply.

We can take a look at a national level here and see that current planning schemes have the potential to yield 131,000 new homes per year for a decade from 2008! This excludes the increase in housing stock from developments with less than 10 dwellings. In the abovelinked OESR report they state that smaller developments of 10 or fewer dwellings accounted for 69.5 per cent of projects at June 2010. This means the estimate of 131,000 new homes accounts for only 40% of the actual supply available under current planning schemes.

Even so, they sum up their analysis of land supply by stating that there was approximately 7–8 years supply of zoned broadhectare land in 2007.

Monday, April 11, 2011

No evidence of supply-side constraints in approvals data

Possibly the central lesson of my previous post was that planning controls and development approvals by local councils are not a factor that limits the quantity of new homes constructed. Council behaviour in these areas could limit housing supply if councils began a system of quotas for approvals. But they don’t. They provide limitations on the location of new supply in their planning instruments, and they approve the quantity of homes demanded by the development industry - which is a reflection of the number of new home sales. Sales volumes of new homes and land determine the rate of supply of new dwellings.

So is there evidence that councils are limiting the supply of new dwelling through their planning controls and approvals processes?

No.

Let’s look at my home town of Brisbane. The following table shows the stock of approved house lots in Brisbane and surrounding local council areas that are yet to be developed (All data from here - Table 1. Excludes building units and retirement homes).

In Brisbane, where broadacre land is arguable more physically constrained, the stock of approved housing lots has remained relatively constant. And as you would expect, in the fringe areas, the stock of new house lots has grown far more rapidly than sales of lots or construction of housing. This indicates that councils approve far more housing lots than the market can absorb.

Yet it is this development approval that many claim is a hold-up to development.

In Brisbane, this reserve stock equates to about two years supply, while in surrounding areas there is between 3 and 10 years supply (Logan City and Somerset respectively) already approved. Of course, there are many thousands more lots that could be approved under existing planning schemes should demand arise.

Remember, this is just the stock of new land developments. If data were more readily available for unit developments there will no doubt be a similar story (in Brisbane attached homes are about 50% of new stock).

The clear message that comes from actual data on planning approvals is that they are not a constraint to supply. This might be one reason why these figures are never mentioned by ‘supply-siders’, even in the most detailed documents outlining supply side concerns in the housing market such as the 2003 Prime Ministers Taskforce on Home Ownership Report.

Saturday, April 2, 2011

8 Economic Lessons on Planning and Housing Supply

The housing bubble debate often leads to claims that town planning controls and approvals processes are a contributing factor to the price boom. It is argued that such controls can constrain the rate of housing supply during periods of high demand, allowing prices to ratchet up. But there is no case for the argument that planning controls can influence the general price level of housing.

For those unfamiliar with property development, the following lessons may be of interest.

Monday, October 4, 2010

Statistics lessons for property people

I have previously posted about the Property Council of Australia’s cowboy approach to statistics to argue for pro-sprawl planning policies on environmental grounds. Now Brian Stewart, CEO of the Urban Development Institute of Australia (UDIA) Queensland, needs a lesson in statistics.

In a recent bulletin to members he criticised the Local Government Association of Queensland’s interpretation of a report they commissioned on factors affecting home prices in South East Queensland.

He questions the conclusion that the AEC report commissioned by LGAQ refutes ‘for all time the spurious arguments of a so-called under-supply of dwellings in the SEQ market’. If he had paid attention in statistics it would be clear to him that this is exactly what the report does.

Although the report is far from an exemplary analysis of key determinants of residential property prices, the authors did estimate six econometric models to seek the determinants of real median house, unit and land prices in SEQ - eighteen models in total. If we quickly browse the report we find just one model, for house prices, not unit or land prices, where any of their supply-side variables is significant in explain real prices.

To be sure, Stewart’s interpretation of the report was poor, and his bulletin misleading, but I still have reservations about the report itself.

Particularly I have concerns about the choice of, and construction of, variables, including location bias in calculating the median prices and using ratios to total stock rather than sales volumes (particularly in the treatment of the FHOG). It seems odd that with 69 data points and 32 variables at hand they had trouble finding significant relationships in the data – could it be their selection was stacked with the wrong variables to explain prices?

One example of the construction of variable is ‘SEQ housing stock per capita’, which is total stock for SEQ at the beginning of the period at the beginning of the analysis (1991) of 734,126, less an allowance for depreciation (about 0.3%), plus new stock completed IN QUEENSLAND in the period. This variable then accumulates over time to represent the stock of housing.

I first hope that the new stock only includes new stock in the SEQ region and that this is a typo. Second, I can’t see how depreciating a dwelling is good accounting. What should be considered is a factor for demolitions, and it would be easy enough to estimate the demolition to new dwelling ratio based on past census data.

These types of errors abound.

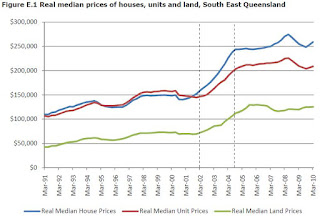

Most importantly I wonder how this controversial variable could be negatively correlated with prices. In the section on housing stock (p13) it shows that dwelling stock per 100 people grew from 38.1 to 41.1 from 1991 to 2006, while real prices grew from around $100,000 to $250,000 in this period (below). Either a) the three other significant variables, the All Ordinaries, unemployment and mortgage rates, explained the most of the change, or b) the variable used in the analysis is the CHANGE IN dwelling stock per person, which was positive but declining over the period.

What is further surprising is the conclusion that the SEQ property market somehow behaves differently to other parts of the country. Given that the analysis failed to explain the behaviour of the SEQ residential property market at all (their final land price model on page 29 had seven variables but just two were significant), one wonders how such conclusions are drawn. I am happy for someone to explain why it is different here (cringe) if they have the evidence to support the statement.

Anyone looking to elastify the supply side should note the report concludes by noting how responsive supply has in fact been to prices:

...the lot stock for SEQ rose from 25,000 during the early part of the decade to reach 50,000 by December 2005 and has stabilised around 54,000 since September 2007. This progression follows the growth in land prices very closely, indicating that supply of undeveloped residential lots has responded to price signals.

In a recent bulletin to members he criticised the Local Government Association of Queensland’s interpretation of a report they commissioned on factors affecting home prices in South East Queensland.

He questions the conclusion that the AEC report commissioned by LGAQ refutes ‘for all time the spurious arguments of a so-called under-supply of dwellings in the SEQ market’. If he had paid attention in statistics it would be clear to him that this is exactly what the report does.

Although the report is far from an exemplary analysis of key determinants of residential property prices, the authors did estimate six econometric models to seek the determinants of real median house, unit and land prices in SEQ - eighteen models in total. If we quickly browse the report we find just one model, for house prices, not unit or land prices, where any of their supply-side variables is significant in explain real prices.

To be sure, Stewart’s interpretation of the report was poor, and his bulletin misleading, but I still have reservations about the report itself.

Particularly I have concerns about the choice of, and construction of, variables, including location bias in calculating the median prices and using ratios to total stock rather than sales volumes (particularly in the treatment of the FHOG). It seems odd that with 69 data points and 32 variables at hand they had trouble finding significant relationships in the data – could it be their selection was stacked with the wrong variables to explain prices?

One example of the construction of variable is ‘SEQ housing stock per capita’, which is total stock for SEQ at the beginning of the period at the beginning of the analysis (1991) of 734,126, less an allowance for depreciation (about 0.3%), plus new stock completed IN QUEENSLAND in the period. This variable then accumulates over time to represent the stock of housing.

I first hope that the new stock only includes new stock in the SEQ region and that this is a typo. Second, I can’t see how depreciating a dwelling is good accounting. What should be considered is a factor for demolitions, and it would be easy enough to estimate the demolition to new dwelling ratio based on past census data.

These types of errors abound.

Most importantly I wonder how this controversial variable could be negatively correlated with prices. In the section on housing stock (p13) it shows that dwelling stock per 100 people grew from 38.1 to 41.1 from 1991 to 2006, while real prices grew from around $100,000 to $250,000 in this period (below). Either a) the three other significant variables, the All Ordinaries, unemployment and mortgage rates, explained the most of the change, or b) the variable used in the analysis is the CHANGE IN dwelling stock per person, which was positive but declining over the period.

What is further surprising is the conclusion that the SEQ property market somehow behaves differently to other parts of the country. Given that the analysis failed to explain the behaviour of the SEQ residential property market at all (their final land price model on page 29 had seven variables but just two were significant), one wonders how such conclusions are drawn. I am happy for someone to explain why it is different here (cringe) if they have the evidence to support the statement.

Anyone looking to elastify the supply side should note the report concludes by noting how responsive supply has in fact been to prices:

...the lot stock for SEQ rose from 25,000 during the early part of the decade to reach 50,000 by December 2005 and has stabilised around 54,000 since September 2007. This progression follows the growth in land prices very closely, indicating that supply of undeveloped residential lots has responded to price signals.

Sunday, September 26, 2010

Lessons for the RBA on their blunt instrument

RBA Governator Glenn "I''l be back - with higher interest rates" Stevens has been softening up the public for his next interest rate move. He warns that his toolkit contains only a blunt instrument, and we will all be affected. I guess if the only tool you have is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail.

... we only have one set of interest rates for the whole Australian economy; we do not have different interest rates for certain regions or industries. We set policy for the average Australian conditions. A given region or industry may not fully feel the strength or weakness in the overall economy to which the Bank is responding with monetary policy. In fact no region or industry may be having exactly the ‘average’ experience. It is this phenomenon that people presumably have in mind when they refer to monetary policy being a ‘blunt instrument.

I think poor old Glenn is taking his hammer to a screw.

While he wisely notes we have one set of interest rates, not one interest rate, he seems to ignore the fact that differentiation of interest rates on debt should reflect the risk for each particular loan. The problem for the RBA is that those who actually lend in the marketplace are failing to properly price the risk premium associated with their particular loans. Housing is surely a risky investment at the moment, yet interest rates do not reflect the risk premium.

The obvious alternative to shifting the whole set of interest rates is to better manage the risk premium rate for a particular industry of concern, or forcefully adjust risks taken with other measures to suit the rates adopted in that industry.

For example, if banks insist on lending for housing at relatively low interest rates, they can reduce risk by keeping lower LVRs and more conservative income estimates. If they won’t do it voluntarily, because they suffer from extreme moral hazard associated with guaranteed government bail-outs, maybe the RBA can seek to have banks better regulated with regards to housing loan risks, particularly qualifying income and LVRs.

At the moment increasing interest rates will simple increase the interest burden on current debts, high risk or not, decrease take up of borrowing for productive purposes, and fail to curb the mispricing of risk and crude lending criteria of housing loans with the major banks.

... we only have one set of interest rates for the whole Australian economy; we do not have different interest rates for certain regions or industries. We set policy for the average Australian conditions. A given region or industry may not fully feel the strength or weakness in the overall economy to which the Bank is responding with monetary policy. In fact no region or industry may be having exactly the ‘average’ experience. It is this phenomenon that people presumably have in mind when they refer to monetary policy being a ‘blunt instrument.

I think poor old Glenn is taking his hammer to a screw.

While he wisely notes we have one set of interest rates, not one interest rate, he seems to ignore the fact that differentiation of interest rates on debt should reflect the risk for each particular loan. The problem for the RBA is that those who actually lend in the marketplace are failing to properly price the risk premium associated with their particular loans. Housing is surely a risky investment at the moment, yet interest rates do not reflect the risk premium.

The obvious alternative to shifting the whole set of interest rates is to better manage the risk premium rate for a particular industry of concern, or forcefully adjust risks taken with other measures to suit the rates adopted in that industry.

For example, if banks insist on lending for housing at relatively low interest rates, they can reduce risk by keeping lower LVRs and more conservative income estimates. If they won’t do it voluntarily, because they suffer from extreme moral hazard associated with guaranteed government bail-outs, maybe the RBA can seek to have banks better regulated with regards to housing loan risks, particularly qualifying income and LVRs.

At the moment increasing interest rates will simple increase the interest burden on current debts, high risk or not, decrease take up of borrowing for productive purposes, and fail to curb the mispricing of risk and crude lending criteria of housing loans with the major banks.

Tuesday, September 21, 2010

Gaming leads to unintended consequences when governments try to stimulate housing supply

Australia’s excessively priced housing gave rise to the housing shortage myth, which in turn led governments at all levels amending planning policies to allow for greater scale of development. Densification, transit-oriented development, growth corridors and other buzz words, were drip fed by property lobby groups to politicians in search of an elixir for the ailing mortgage belt voter. The media, and by extension the public, bought into this supply-side ‘solution’ to housing affordability. Very few realised the irony of the situation – a policy on housing affordability that was a gift to existing property owners and ‘land banking’ developers.

The aggressiveness of changes to planning instruments to allow for greater heights and densities, and allow fringe areas into the urban footprint, provided opportunities to profit simply from speculation on the next change to the planning scheme. For landowners it became more profitable to wait three years for the local government to update the planning scheme to allow greater density of development, than to actually develop the site.

One example, South Brisbane, epitomises this situation.

Expectations were for this pattern to continue. A landholder in this area recently mentioned they have no reason to sell or develop when the council keeps increasing the value of their land by changing the planning scheme. Landholders are gaming the Council, waiting for a signal that the gifts will soon expire before selling up to developers.

Maybe that signal is here.

The State government has intervened in the latest round of planning scheme changes to request the proposed height limits be cut back – where 12 storeys was proposed, they will allow seven.

For anyone aware of the standoff taking place the flood of development sites onto the market in the month since the State government decision would come as no surprise. Who would have thought reducing height limits would promote so much development activity?

The moral of this story is that certainty (or lack thereof) can greatly change real outcomes. Economists often foolishly assume that all government decisions are taken at face value by the marketplace. Few realise the time element and that parties affected will already be anticipating the next decision, or gambling on a political backflip.

UPDATE: More evidence of rewarding land banking rather than productive land use, from the Local Government Association of Queensland -

The aggressiveness of changes to planning instruments to allow for greater heights and densities, and allow fringe areas into the urban footprint, provided opportunities to profit simply from speculation on the next change to the planning scheme. For landowners it became more profitable to wait three years for the local government to update the planning scheme to allow greater density of development, than to actually develop the site.

One example, South Brisbane, epitomises this situation.

At this prime location, within a stone's throw of the CBD, the previous limits of 12 and eight storeys were already conservative.The planning scheme for this precinct has changed from allowing four storeys, to seven storeys, then proposing eight storeys, then twelve storeys in the latest draft plan, and now the UDIA is calling to increase the heights much further. With the approval of a 30-storey tower adjacent to Milton railway station, one could assume there is a long way to go in this saga.

Expectations were for this pattern to continue. A landholder in this area recently mentioned they have no reason to sell or develop when the council keeps increasing the value of their land by changing the planning scheme. Landholders are gaming the Council, waiting for a signal that the gifts will soon expire before selling up to developers.

Maybe that signal is here.

The State government has intervened in the latest round of planning scheme changes to request the proposed height limits be cut back – where 12 storeys was proposed, they will allow seven.

For anyone aware of the standoff taking place the flood of development sites onto the market in the month since the State government decision would come as no surprise. Who would have thought reducing height limits would promote so much development activity?

The moral of this story is that certainty (or lack thereof) can greatly change real outcomes. Economists often foolishly assume that all government decisions are taken at face value by the marketplace. Few realise the time element and that parties affected will already be anticipating the next decision, or gambling on a political backflip.

UPDATE: More evidence of rewarding land banking rather than productive land use, from the Local Government Association of Queensland -

The LGAQ today criticised a key provision of legislation introduced to state parliament on Tuesday which retained a 40 per cent rate subsidy for large companies holding big tracts of land approved for development but not yet formally subdivided.

The money at stake is not the issue here. The issue is the massive contradiction of rewarding developers for not sub-dividing land to increase supply when the state government says it is championing housing affordability issues

Friday, September 17, 2010

A closer look at Australian incomes and predictions from Google Trends

Income distribution fascinates economists. The release of the new ABS personal income estimates for small areas gives a complete picture of the geographical spread of incomes in this country for the first time. Given the amount of media attention to Australia’s recent economic success, these figures surprised me. They are extremely low. Australia’s average gross personal income for 2007/08 was $44,402 or about $853 per week.

Let’s take a closer look.

The calculation of this income figure is an average of individuals with any of the following sources of income in the 2007/08 financial year -wage and salary income, investment income, unincorporated business income, superannuation and annuity income. It does not include individuals whose sole income comprised government benefits. It therefore includes all casual, part-time and full-time workers, self-funded retirees and business owners. What it doesn’t include are the government benefits many of these groups may also receive.

If government benefits received by this group were included the average would be higher. After tax incomes would, however, be much lower.

It is important to be clear that these are gross incomes after deducting losses, remembering that there are 1.7million residential property investors with net losses in 2007/08 of $8.6billion. Averaging across the population does not clearly show the diversity of investment income and the severity of many negative investment incomes.

We must also note that these are all average numbers, and as is typical for these types of (assumed) distributions, the median income would be much lower.

Why is this important?

Much of the mainstream economic establishment has latched on to the idea that incomes have been rapidly rising in Australia, yet the data does not to support this optimistic view.

If we examine, for example, total earnings of full time employees, we can see that in the period 1995-2010, annual growth in before tax total earnings was a mere 3.9%. In real terms, a 1.3% annual increase in full time wages since 1995. Total earnings of fulltime employees in 2007/08 were $67,860 (wage plus other income), and from recent data, it looks like private sector earnings are pretty flat since then. That’s about $52,000 after tax.

The ABS capital city house price index on the other hand, rose by an annual rate of 9.4% since 2002. RPData-Rismark currently has Australia’s median dwelling price (detached and attached) at $405,000 and the ‘trimmed mean’ home price at $435,000.

Anyone who claims home prices are rising in line with incomes either has not seen the data, or is being intentionally deceptive. The RBA can be counted amongst this group.

Australia’s current housing situation is truly unsustainable. It would take two above average fulltime workers to buy one median priced dwelling. If they want to live in or near a capital city, the situation is more severe.

With an income picture less rosy than many make out, it is quite clear that current elevated house prices are not due to owner occupier demand - there is simply not enough income for that to be true. They have risen strongly through speculative investment decisions backed by government support (including negative gearing). Anyone who claims that home prices are stable due to incomes fails to realise that prices are determined by investors who can abandon the market in droves as soon as returns start looking bleak.

Moving on.

Google has an uncanny ability to predict the future. Google Trends allows users to plot search popularity over time for any search term you like. I have borrowed this idea from various other sites, but what prompted me to post it was a line I read that went something like - ‘once the mainstream media is talking about a housing bubble it is ready to crash.’ As you can see below, this was definitely true in the US. The recent attention to Australia’s precarious housing situation is a worrying sign for those recently leveraged into the market.

Sunday, August 22, 2010

Living in a bubble

Morgan Stanley’s Gerard Minack aptly uses the phrase ‘living in a bubble’ as the title of his research note about Australia’s housing market. Minack’s conclusion is that Australian housing is overvalued, but he sees prolonged stagnation rather than a dramatic pop of the price bubble - I expect that the real returns on residential investment will be negative over the next decade.

I want to highlight a few key charts from the research note. The first is a comparison of prices to rents, showing a massive increase above the long run average since 2000 (I believe this figure is price divided by annual gross rent divided by 100). One could call on interest rates as an explanation, but mortgage interest rates have actually been increasing over much of that period.

The second chart is a comparison of the value of the housing stock to household income, which further supports this claim that home prices are 30-40% above average levels.

I want to highlight a few key charts from the research note. The first is a comparison of prices to rents, showing a massive increase above the long run average since 2000 (I believe this figure is price divided by annual gross rent divided by 100). One could call on interest rates as an explanation, but mortgage interest rates have actually been increasing over much of that period.

The second chart is a comparison of the value of the housing stock to household income, which further supports this claim that home prices are 30-40% above average levels.

The next chart is one that compares the share of household debt by income level. One of the RBA’s claims has been that Australia’s housing market is stable because most debt is held by high income earners - ...our assessment is that the increase in debt has broadly been concentrated in the hands of those generally more able to service it. This is identical the the US situation in 2007.

Sunday, August 1, 2010

Quick housing update and forecasts

The residential property bears breathed a sigh of relief with the release of the monthly RPData hedonic price index for June - down 0.7% (with Brisbane prices down 1.3%). The bulls however are happy enough with the 20% capital growth performance since June 2009.

In light of this, Steve Keen has laid out his forecast of things to come in residential property:

Firstly, with an increased stock of unsold houses on the market, buyers are likely to take yet more time to make a decision—which will add further to the backlog. If prices are falling, why hurry? The urgency will leave the buy side.

Secondly, so-called investors—whom I prefer to call speculators, since 90% of them have bought existing properties rather than built new ones—will start to consider whether they should swap from the buy side to the sell side. After all, no-one in their right mind buys an investment property in Australia for the rental returns: it’s capital gains or nothing DownUnder. Do you capitalize on gains to date, or hang on hoping that the upward trend will re-assert itself once more?

I expect these two processes to lead to an accelerating rate of decline in house prices now, as they did in the USA when “Flip That House” ceased being a winning trade.

Chris Joye has made a typically broad prediction:

Rismark had been forecasting a substantial deceleration in housing conditions back to single-digit annualised growth rates since October 2009. Over the long-run, house prices track purchasing power quite closely. Disposable household incomes were only projected to rise by about 5 per cent in 2010. We’ve had 4.7 per cent growth in dwelling values in the year-to-date. We do not, therefore, expect to see the market rise much further over the remaining year subject to labour market conditions and the course of monetary policy.

Interestingly, Joye notes the decline in housing credit outstanding, but does not seem to believe this will strongly influence prices in the near term.

Finally, over at Delusional Economics we have this gem:

There is no "soft landing" for a debt driven economy that suddenly decides to shun debt

Monday, July 19, 2010

Is residential property Super?

The retirement plans of working families may soon succumb to Australia's residential property mania. If Chris Joye had his way, Australian super funds would invest in the emerging residential equity market to diversify their portfolios against highly correlated domestic and global equities markets. The argument for this move is summarised below.

Investors, such as super funds, get extremely low-cost, highly enhanced and very long-dated exposures to what has, during the past three decades (including the recent calamity) been the largest and best performing of all investment classes: residential real estate. Historically, investors have only been able to access highly concentrated, risky development-style holdings comprising small parcels of properties that incur heinous transaction costs of about 12.5 per cent. By investing in a portfolio of thousands of shared equity interests, super funds could avoid all of these costs and secure the low risk diversification that they have never had before. Independent actuarial analysis suggests that about 15 to 30 per cent of all super fund capital should, in theory, be allocated to housing, in part because its returns are so unrelated to the performance of other investments. Compare the 50 per cent plus losses in shares and listed property trusts in the past year with the fact that the RP Data-Rismark Australian House Price Index has tapered by only -0.8 per cent. (emphasise added)

Is this idea worth embracing? Or to put it another way, how many people would actively choose to invest superannuation in the residential property market?

Super funds investing in residential property equity face a couple major of problems in my view:

1. decreasing the diversity of investor portfolios, and

2. moral hazard associated with residential equity finance.

Investors, such as super funds, get extremely low-cost, highly enhanced and very long-dated exposures to what has, during the past three decades (including the recent calamity) been the largest and best performing of all investment classes: residential real estate. Historically, investors have only been able to access highly concentrated, risky development-style holdings comprising small parcels of properties that incur heinous transaction costs of about 12.5 per cent. By investing in a portfolio of thousands of shared equity interests, super funds could avoid all of these costs and secure the low risk diversification that they have never had before. Independent actuarial analysis suggests that about 15 to 30 per cent of all super fund capital should, in theory, be allocated to housing, in part because its returns are so unrelated to the performance of other investments. Compare the 50 per cent plus losses in shares and listed property trusts in the past year with the fact that the RP Data-Rismark Australian House Price Index has tapered by only -0.8 per cent. (emphasise added)

Is this idea worth embracing? Or to put it another way, how many people would actively choose to invest superannuation in the residential property market?

Super funds investing in residential property equity face a couple major of problems in my view:

1. decreasing the diversity of investor portfolios, and

2. moral hazard associated with residential equity finance.

Sunday, July 11, 2010

Generations of housing affordability

The degradation of housing affordability is widely acknowledged, but unfortunately mainstream explanations miss the fundamental stories of easy credit and tax rules encouraging property speculation.

One of the best collections of Australian residential property analysis on the web has emerged at The Unconventional Economist. Leith's latest article explores changes to housing affordability since the 1970s and the key drivers behind the change.

He summarises the article as follows:

One of the best collections of Australian residential property analysis on the web has emerged at The Unconventional Economist. Leith's latest article explores changes to housing affordability since the 1970s and the key drivers behind the change.

He summarises the article as follows:

- It is the demand for, and supply of, credit that is the key determinant of house prices. Whilst demand-side factors such as tax concessions, benign economic conditions, and population growth might increase people's willingness to borrow for property, ultimately, if you cannot obtain the finance, you cannot pay a high price. Similarly, tight housing supply would have little impact on house prices when credit is not readily available.

- Lower interest rates and easy credit do not make houses more affordable. Rather, they quickly get capitalised into house prices, increasing the amount that home buyers must borrow.

- When examining interest rates and their effect on housing affordability, it is real interest rates (i.e. the mortgage interest rate less inflation) that matters. Whilst mortgage interest rates averaged a seemingly high 9% in the 1970s, due to high inflation (averaging 11%), real interest rates were negative, resulting in borrowers' mortgage debt being 'inflated away'.

- Importantly, be very weary of offers of more credit and the promise that it will "improve housing affordability". Any scheme that increases home buyer's borrowing capacity, such as shared equity loans and the Never Ending Mortgage, will instead fuel further house price growth, thus eroding affordability.

- Beware the property spruiker. Always be sceptical when reading property-related articles in the press, or when listening to politicians talk about housing affordability. Whilst they might, on the surface, sound reasonable, they are often talking their own book. Instead, think critically about their motives and who their constituents really are.

Tuesday, July 6, 2010

Effects of dwelling composition in the property market

Much popular property market analysis based on flawed principles. A secret to identifying rubbish analysis is to note the following meaningless buzzwords and phrases; underlying demand, housing shortage, urbanisation or population growth.

Furthermore, the size of existing homes changes over time with renovations and extensions. It has been widely acknowledged that many home owners have chosen to renovate instead of relocate in their search for more spacious accommodation. It is easy enough to imagine a street of heritage homes, for example, being renovated and extended to allow a large increase in the population of the street. No new homes, plenty of new people, and no housing shortage.

These buzzwords are based on a fallacy. The problems they have in common is that they are quantity based (thus ignore prices), and they ignore changes in the composition of dwellings.

Commentators calculate underlying demand by dividing the quantity of population growth in a given period by the average occupancy rate. This is supposed to give a measure of quantity of dwellings that ‘should’ be constructed of the period. Unfortunately, the occupancy rate itself changes over time. It has been declining dramatically for three decades. If the trend continues we may soon be able to calculate a housing shortage even if we build a new home for every new person!

Calculating a ‘housing shortage’ is then a simple matter of subtracting the number of dwellings constructed over a time period from the underlying demand. The graph below shows the result of this calculation for Australian from 1994 – 2009 using quarterly data (and the occupancy rate at each quarter – not the current occupancy rate).

Spruikers use this measure to justify the likelihood of price gains, yet the price changes observed seem to in fact be inversely correlated to underlying demand. We had a price boom from 2002-2004 at the same time as a housing surplus!

These measures also fail to acknowledge the heterogeneity of housing. Counting a studio apartment and a 5-bedroom house as equal in the calculation of a housing supply is a mere fallacy. Clearly these two different dwellings will house different numbers of people.

Furthermore, the size of existing homes changes over time with renovations and extensions. It has been widely acknowledged that many home owners have chosen to renovate instead of relocate in their search for more spacious accommodation. It is easy enough to imagine a street of heritage homes, for example, being renovated and extended to allow a large increase in the population of the street. No new homes, plenty of new people, and no housing shortage.

What we have seen in the latest property boom is a continuation of the trend to build larger homes with more bedrooms, while the occupancy rate continued to decline. At some point you would expect the occupancy rate to bounce back before we all ended up living alone with three spare bedrooms. And it did.

The average number of persons per household has declined from 3.1 in 1976 to 2.6 in 2007-08. In the same period, the proportion of dwellings with four or more bedrooms has risen from 17% to 29% and the average number of bedrooms per dwelling has increased from 2.8 to 3.1.

In 2007-08, most households enjoyed relatively spacious accommodation. For example, 86% of lone-person households were living in dwellings with two or more bedrooms; 75% of two-person households had three or more bedrooms; and 35% of three-person households had four or more bedrooms. Over a fifth (21%) of three-bedroom dwellings, and 8% of four-bedroom dwellings, had only one person living in them

Important demographic reasons explain why we should expect the declining occupancy trend to come to an end. The aging population including baby-boomers downgrading is a key way in which this will occur (others include a rise in share housing by the forever young Gen-Y who are delaying family formation).

For example, the parents of a family whose adult children have moved out with friends or partners might find that the upkeep of a large house conflicts with their ‘grey nomad’ retirement plans. They can sell their 5-bedroom house and move into a new 2-bedroom unit, pocketing the price difference for their retirement.

In this scenario, the construction of a 2-bedroom apartment resulted in a 5-bedroom home being available to meet the housing needs of population growth.

The final fallacious buzzwords that provide property bulls justification for their position are urbanisation and population growth. If we were discussing any other good or service the pattern of habitation would be of little consequence to the expected prices. Increased urbanisation doesn’t drive up the price of food, petrol or any other goods – nor does population growth.

Increased urbanisation can lead to increased land prices, but that doesn't necessarily lead to increases in median housing price measures due to compositional change. Because new dwellings in outer areas are typically inferior locations to existing homes, the prices one would expect for identical dwellings in new estates would be lower. Since there is more land at the fringes of cities, we would expect that proportionally more cheaper dwellings to be added to the mix of housing. Prices for existing homes can rise, but due to the greater proportion of housing in outer areas in the mix, a price index can remain flat at the same time.

The table below shows a hypothetical city made up of identical dwellings, where new supply is mostly added at the fringes. Even though the price of each individual dwelling increases 10% over the period, a city-wide mean price index would remain flat due to the greater proportion of cheaper dwellings. The same effect can happen with new apartments in traditional detached housing areas.

Also constantly overlooked is the fact that urbanisation can only occur AFTER new urban dwellings are constructed unless driven by an increase in occupancy rates. Until the end of 2005 prices was rising fast, urbanisation and population growth were occurring, but the occupancy rate continued to decline.

Increased urbanisation can lead to increased land prices, but that doesn't necessarily lead to increases in median housing price measures due to compositional change. Because new dwellings in outer areas are typically inferior locations to existing homes, the prices one would expect for identical dwellings in new estates would be lower. Since there is more land at the fringes of cities, we would expect that proportionally more cheaper dwellings to be added to the mix of housing. Prices for existing homes can rise, but due to the greater proportion of housing in outer areas in the mix, a price index can remain flat at the same time.

The table below shows a hypothetical city made up of identical dwellings, where new supply is mostly added at the fringes. Even though the price of each individual dwelling increases 10% over the period, a city-wide mean price index would remain flat due to the greater proportion of cheaper dwellings. The same effect can happen with new apartments in traditional detached housing areas.

Also constantly overlooked is the fact that urbanisation can only occur AFTER new urban dwellings are constructed unless driven by an increase in occupancy rates. Until the end of 2005 prices was rising fast, urbanisation and population growth were occurring, but the occupancy rate continued to decline.

Analysis of the property market should focus on returns in comparison with other investments, with renting (user cost approach), and historical returns. Counting dwellings, and implying demand from population growth or urbanisation is problematic due to compositional factors.

Wednesday, June 30, 2010

End of Financial Year Wrap Up

HOUSING MARKET

All things considered, the Australian housing market looks ready to dive. My conversations with real estate agents are the only ones they've been having - no buyers are willing to even make a call at the moment. Home lending is down, prices are taking a u-turn, sales are down, and first home buyers are lost somewhere in the mist of winter mornings.

There has been some interesting analysis from Steve Keen lately, along with the more spruikung from renouned pro-housing, anti-commerical property, anti-shares, anti-all other investments, man on the spot Chris Joye.

My outlook – a surprise drop in home prices leading a significant decline in economic activity in Australia. The Reserve Bank will act promptly to reduce interest rates while pointing fingers to troubles abroad. Bulls will then promptly join the finger pointing, noting how exceptional strong Australia’s housing market has been and the supply shortages still threaten to create future unaffordable housing.

Aspirational home buyers should take a look at a true financial comparison of home ownership and renting before making any major decisions.

AUSSIE DOLLAR

The Australian dollar will not be safe. Think September 2008 all over again.

BLOGOSPHERE

Two new blogs worthy of mention are Delusional Economics, where you will be enlightened by some straight talking no-nonsense commentary, and a special mention for the Unconventional Economist for some very high quality articles on the Australian property market.

REBOUND EFFECTS

My attitude on helmet law rebound effects has been seen as quite controversial. But for those interested this site articulates my position quite accurately.

Experience shows helmets give only limited head protection. Studies in Australia show some prevention of superficial injuries (such as scalp lacerations) but only marginal prevention of “mild” head injuries and no effect on severe head injuries or death. When helmets were made compulsory in Australia, admissions from head injury fell by 15-20%, but the level of cycling fell by 35%.

To summarise, helmet laws led to a major decline in cycling. Fewer cyclist on the road decreased awareness of them by drivers, leading to cycling in general becoming less safe. Further, helmets themselves offer limited head protection in a limited number of crash circumstances - a helmet doesn't help much if you go over the handle bars and land on your face for example. And if you get hit by a truck (the classic pro-helmet argument) you are stuffed whatever you are wearing on your head.

THE LAST WORD

If the financial and economic circus of 2009/10 has been all too mauch, it might be time for a holoiday. For those who take this advice but want to optimise their holiday time, have a read of this quality article.

All things considered, the Australian housing market looks ready to dive. My conversations with real estate agents are the only ones they've been having - no buyers are willing to even make a call at the moment. Home lending is down, prices are taking a u-turn, sales are down, and first home buyers are lost somewhere in the mist of winter mornings.

There has been some interesting analysis from Steve Keen lately, along with the more spruikung from renouned pro-housing, anti-commerical property, anti-shares, anti-all other investments, man on the spot Chris Joye.

My outlook – a surprise drop in home prices leading a significant decline in economic activity in Australia. The Reserve Bank will act promptly to reduce interest rates while pointing fingers to troubles abroad. Bulls will then promptly join the finger pointing, noting how exceptional strong Australia’s housing market has been and the supply shortages still threaten to create future unaffordable housing.

Aspirational home buyers should take a look at a true financial comparison of home ownership and renting before making any major decisions.

AUSSIE DOLLAR

The Australian dollar will not be safe. Think September 2008 all over again.

BLOGOSPHERE

Two new blogs worthy of mention are Delusional Economics, where you will be enlightened by some straight talking no-nonsense commentary, and a special mention for the Unconventional Economist for some very high quality articles on the Australian property market.

REBOUND EFFECTS

My attitude on helmet law rebound effects has been seen as quite controversial. But for those interested this site articulates my position quite accurately.

Experience shows helmets give only limited head protection. Studies in Australia show some prevention of superficial injuries (such as scalp lacerations) but only marginal prevention of “mild” head injuries and no effect on severe head injuries or death. When helmets were made compulsory in Australia, admissions from head injury fell by 15-20%, but the level of cycling fell by 35%.

To summarise, helmet laws led to a major decline in cycling. Fewer cyclist on the road decreased awareness of them by drivers, leading to cycling in general becoming less safe. Further, helmets themselves offer limited head protection in a limited number of crash circumstances - a helmet doesn't help much if you go over the handle bars and land on your face for example. And if you get hit by a truck (the classic pro-helmet argument) you are stuffed whatever you are wearing on your head.

THE LAST WORD

If the financial and economic circus of 2009/10 has been all too mauch, it might be time for a holoiday. For those who take this advice but want to optimise their holiday time, have a read of this quality article.

Tuesday, June 22, 2010

Negative Gearing Exposed

By far the best analysis of the impact of negative gearing on the residential property market is found here. The myths that negative gearing increases the supply of rental accommodation and keeps rents down are exposed, and some quality suggestions for improving housing affordability are made. Highly recommended.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)