Let us look at the theory to see why the productivity gains from Australia’s pursuit of competition reform have been so hard to come by. Oliver Williamson’s 1968 model of the competition-coordination tradeoff is a good starting point.

The assumptions in Williamson’s model are that the monopoly industry has a lower marginal cost than competitive firms, that the monopolist sets their profit maximising price according to traditional economic theory, and that in a competitive market firms set their prices at marginal cost.

The graph below shows the resulting welfare implications of this model.

In this situation, while the competitive firms face higher costs (MC2), they set a price lower than the profit maximising monopolist (at P2 instead of P1). The welfare implication is that the area A is transferred from producer to consumer surplus, area B is the loss of producer surplus due to coordination costs, and area C is the gain to consumer surplus. There is a net loss of social surpluses (including all producer surplus) from competition in this model, however there are significant gains to the consumer surplus (areas A and C).

For a net gain to consumers in this model, two conditions need to be met:

1. The profit maximising price of the monopolist is higher that the marginal cost to the competitive producer (MC2 < P1), and

2. The competitive producers set prices at marginal cost (P2=MC2)

Unfortunately, neither of these conditions can be known in advance. In fact, if we drop just the second assumption, which has been proven many times to be far from realistic, the chances of a competitive market generating greater surpluses than a profit seeking monopolist greatly diminishes. In the above diagram this would mean that P2 is somewhere above MC2 (and of course we still don’t know if MC2 is below P1).

Costs associated with vertical separation and competition can be significant, including:

1. Coordination costs and risks of contract development and enforcement

2. One-off reorganisation costs

3. Costs of regulation and oversight and potentially unpredictable regulatory interpretations and legal determinations

4. Marketing and advertising costs for competitive firms

5. Insurance costs (government entities would typically self insure at a lower cost)

6. Profits (not necessary for a government entity)

Additionally, incentives change under a competitive structure. The legal profession and regulators now have a vested interest in promoting complex regulation while competitive firms may feel ‘too big to fail’ and take undue risk and malinvestment.

Another incentive change as a result of vertical separation is the classic hold-up problem (a type of path dependence I have discussed previously). Although the classic GM Fisher Body problem has apparently been resolved and was not in fact an example of this problem, there are clearly cases of technology change and investment where vertical integration sheds risk and reduces costs. For example, if railways were vertically separated so that multiple companies trains operated on a monopolist's track, new track technology (materials, gradient or other change) could not be adopted without corresponding investment in trains to run on new lines. The first mover to the new technology can be held to ransom by the second mover, thus the profit maximising outcome is for neither side to make a move.

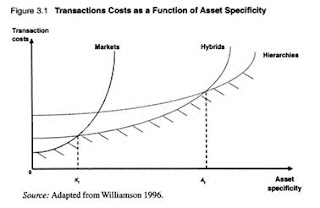

Let us now return to the coordination costs resulting from separation. Increased transaction costs result partly from contract negotiation, but also from risk. The graph below shows that the more specialised a fixed asset, the higher the transaction costs (and risk) for the vertical separated supplier. Markets provide efficient transaction cost outcomes when very large capital investments are not highly specialised. This is not the case for most infrastructure networks.

There is of course one key benefit from competition that is not represented in these models – it is the benefit of simply having consumer choice from competition. Consumers (or intermediate producers) can use their power to choose, which provides incentive for competitive firms to innovate not just on cost saving, but on service provision. For example premium and budget services could emerge (think airlines).

One must also carefully define competition. The power of consumer choice exists even with apparent natural monopolies. For example, rail freight competes with cargo shipping, road haulage, and even air freight. There is a limit to the ability of a monopoly rail line to manipulate freight prices in light of the alternatives available. There are even alternatives to centralised electricity. In remote areas on-site electricity generation is still common. Households and businesses have the opportunity to invest in their own generation capacity should the network supplier exhibit monopoly pricing behaviour (solar, diesel, wind). Water can be sourced from rain water, bores, and recycled on site, while composting toilets are an emerging trend for the environmentally conscious.

The Austrian School’s “permanent economic process” of competition follows similar logic, and argues that “market dominance is always necessarily temporary in the absence of monopoly-creating government regulation.” All industries, no matter their cost characteristics and number of competitors, are exposed to risks from new technologies and potential competitors. It is only government designation that creates true monopolies and stifles the permanent process of competition. Such designations lead to an early 20th century trend, where “virtually every aspiring monopolist in the country tried to be designated a "public utility," including the radio, real estate, milk, air transport, coal, oil, and agricultural industries, to name but a few.”

The Austrians see little benefit from public provision of any good. Yet what they fail to acknowledge it that underpinning their vision is the assumption of competitively priced access to public property – such as roads and underground space for water and sewer, and rights to erect power lines – which due to the complexity and diversity of costs to the public, can never be appropriately priced. This feature means that governments will always retain monopoly control of access to public space which forms a key production stage (this idea will be revisted in a later post).

Before leaping onto the competition bandwagon, one should evaluate the limits of monopoly behaviour due to broader competitive threats including technology change. One should acknowledge that on most occasions, monopoly power will still be held by government in some form. Furthermore, one should look to history to examine reasons for the existence of the monopoly in the first place. This historical perspective is the topic of Competition Series Part III.

This is another good example of why the Austrians are good old-fashioned wrong. How do you get from the statement that no public goods should exist without also thinking that anything can be appropriately priced? Is there simply no such thing as a too-hard basket for your average Austrian?

ReplyDeleteThere are some very good situations in which a natural monopoly should exist, it's just a matter of making sure that they behave as if they were a perfectly competitive firm rather than telling them to just get on with it.

Nice one Customs Clearance & Less-than Container Load services

ReplyDelete